Research Spotlight- Dr Freya Harrison

I moved to SLS in August to start my first fully independent academic position. I am already making new connections with colleagues in SLS, the Medical School and local NHS Trusts to support my work on two exciting research projects: a new lab model of multi-species biofilm in cystic fibrosis, and an interdisciplinary, international consortium that is working to hunt out new antibiotics in medieval medical books.

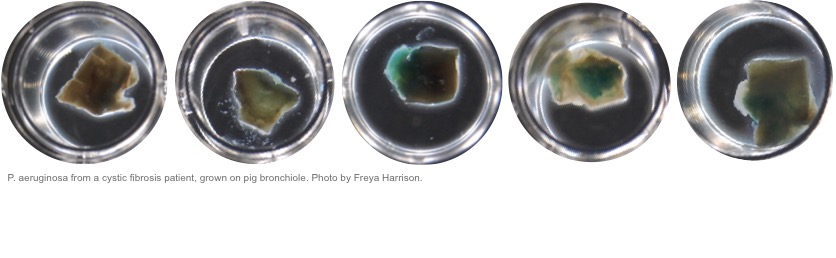

Like most chronic, antibiotic-resistant infections, lung infections in cystic fibrosis are caused by complex biofilm communities of pathogens that interact and evolve over long periods inside the patient. We still know very little about how microbial ecology and evolution in these mixed infections drives persistence and resistance. I have developed a model which could help to address this knowledge gap and perhaps suggest more effective ways of treating these lethal infections. I dissect small pieces of tissue from pig lungs, which I source from a local butcher. I infect the tissue with pure cultures or mixed consortia of pathogenic bacteria and then culture it in conditions that closely mimic chronically-infected cystic fibrosis lungs. This lets me study pathogen community ecology and pathology in a very realistic context. Because the lungs I use are a byproduct of the meat industry, this model is also very ethical. In the future, its wider adoption could reduce the use of live animals in infection research.

I am also part of a team of microbiologists, philologists, medicinal chemists and pharmacologists who are working together to understand the history of infectious disease. Most antimicrobials derive from natural compounds, so ethnopharmacology - the study of traditional medicines - is therefore an important tool in the development of new antibiotics. But ethnopharmacology has paid little attention to European historical remedies, nor do ethnopharmacologists generally try to reconstruct complex historical remedies – which often involve several ingredients. Medieval European manuscripts contain numerous complex remedies for microbial infections, and the “AncientBiotics” team has already conducted a detailed pilot study of an Anglo-Saxon remedy for eye infection. The remedy kills various different strains and clinical isolates of bacteria that cause antibiotic-resistant soft tissue infections – including Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Importantly, the recipe’s efficacy requires us to prepare and combine ingredients exactly as specified by the text. This means that we now have a lot of work to do in order to work out what interesting chemistry is happening inside this cocktail to generate active compounds! It also suggests that there could be many other historical antibiotic “cocktails” that could yield effective antimicrobial compounds. We are datamining old medical books in order to suggest which natural materials we should investigate for antibiotic potential.

I am excited to see how my work will evolve as I settle into SLS and to the Warwick research community. The start-up support given by SLS will be invaluable over the next couple of years as I develop external funding bids and build up my research group. I am also looking forward to taking on my first Warwick students for undergraduate projects, Doctoral Training Partnership (DTP)/Doctoral Training Centre (DTC) rotation projects and PhDs in 2017.

If you would like more information on my work please visit my website.