Midlife crisis

Andrew Oswald examines the midlife crisis shared by man and ape

|

|

APES' MIDLIFE CRISIS

My latest research project on the psychological well-being of great apes – admittedly an improbable subject for economic study - represents one of the most interesting academic forays of my career.

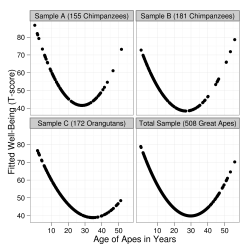

Apes experience a U-shape in ‘happiness’ through their life in the same way that humans do, our paper shows. Happiness levels are generally high in youth, plummet in middle age, and return to high levels again in life’s later years. We have long known this is true for humans. Now, the work of an unconventional collaboration - straddling economics, psychology, primatology and behavioural science - published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that the same is true for orang-utans and chimpanzees.

Apes experience a U-shape in ‘happiness’ through their life in the same way that humans do, our paper shows. Happiness levels are generally high in youth, plummet in middle age, and return to high levels again in life’s later years. We have long known this is true for humans. Now, the work of an unconventional collaboration - straddling economics, psychology, primatology and behavioural science - published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that the same is true for orang-utans and chimpanzees.

A long-standing puzzle provides the intellectual background for this finding. Why is it that humans seem to have a ‘midlife crisis’? An approximately U-shaped pattern in happiness and mental health has been found repeatedly in modern human data. Our paper seems to show that our midlife depressions are not necessarily the exclusive product of the pressures of modern human existence. We are tempted to think that our middle-year troubles are the result of the stress of modern lives conducted in a modern fashion – replete with mortgages that must be paid and mobile phones that must be answered. Yet Great Apes experience the same midlife trough, though they do not face the pressures we tend to blame. While our research doesn’t rule out these economic and social events as sources of stress and anxiety, it does raise the notion that biology may play a part.

We study 508 great apes in zoos across the world. The lifespan of really long-lived apes is about 50 to 55 years, and their psychological well-being reaches a low in the mid- to late 20s. Of course, for humans the lifespan of really long-lived people is about 100 years or just over. Humans’ psychological well-being reaches a minimum around their mid-40s to early 50s, research has shown. Hence, an interesting degree of symmetry emerges between human and non-human primates.

You might think, reasonably enough, that measuring the happiness of apes is not possible. We approach the task as follows:

You might think, reasonably enough, that measuring the happiness of apes is not possible. We approach the task as follows:

The well-being of apes is assessed by independent people who rate apes using a four-item questionnaire based on human subjective well-being measures, but modified for use in nonhuman primates. Item 1 rates the degree to which a subject is in a positive versus negative mood. Item 2 rates how much pleasure the subject derives from social situations. Item 3 rates how successful the subject is in achieving his or her goals. Item 4 asks the person doing these ratings to indicate how happy he would be if he were that subject for a week. The scores are then summed. This questionnaire is becoming a well-established method for assessing well-being in nonhuman primates, and there is evidence for the measure’s objective validity.

What is it about the middle stages of life that we and our ape cousins find difficult? Currently, it remains a mystery. Researchers have known for two decades that, in human data, the U-shape in happiness and mental health through life has nothing to do with having young children in the house, divorce, income, job promotion, and the rest. Until recently, it had been presumed by social scientists that the U-shape might be the result of some socioeconomic forces that we had not identified. But the U- shape seems to have far deeper origins.

Our research suggests that the mid-life crisis, so common in everyday conversation, is a true phenomenon and that it lies so deep within us that it may even have a biological cause. These issues invite and deserve further scrutiny. We still have an enormous amount to learn about ourselves and about the large primates.

Our research suggests that the mid-life crisis, so common in everyday conversation, is a true phenomenon and that it lies so deep within us that it may even have a biological cause. These issues invite and deserve further scrutiny. We still have an enormous amount to learn about ourselves and about the large primates.

The idea for this unconventional research project surfaced when I happened upon an article about research conducted by psychologist Alex Weiss at the University of Edinburgh. A year ago, I called him on the phone, told him that my request might seem strange, and asked if he had data on the happiness of monkeys.

“I prefer to call them by their more accurate name: the great apes,” he told me in that first conversation. “What do you have in mind?”

Thus it began, and we managed to keep the dialogue going across the miles and across the various academic disciplines. The three other members of the team on the paper – James E. King, Miho Inoue-Murayama, and Tetsuro Matsuzawa - are primatologists and behavioural scientists from the University of Arizona and the University of Kyoto. One marker of the modern world is that I have never met those co-authors; we have only communicated by e-mail.

Alex and I met up some months after the initial phone call, in an old Edinburgh restaurant with a polished, sloping wood floor, but the bulk of our exchanges have taken place in the electronic fashion. My Warwick email system tells me that since that strange first phone call, the two of us have exchanged 467 e-mails – a large number, indeed, but one that only begins to scratch the surface of a complex topic that merits more exploration.

About the author

|

Andrew Oswald is a professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Warwick and a senior fellow with the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy (CAGE). His work lies mainly at the border of economics and behavioural sciences, but now appears on occasion to venture into primatology. |

“Evidence for a ‘Midlife Crisis’ in Great Apes Consistent with the U-Shape in Human Well-Being,”![]() by Alexander Weiss, James E. King, Miho Inoue-Murayama, Tetsuro Matsuzawa, and Andrew J. Oswald is forthcoming in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

by Alexander Weiss, James E. King, Miho Inoue-Murayama, Tetsuro Matsuzawa, and Andrew J. Oswald is forthcoming in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.