Myths of the Great War

A century after World War I began, its lessons remain widely misunderstood.

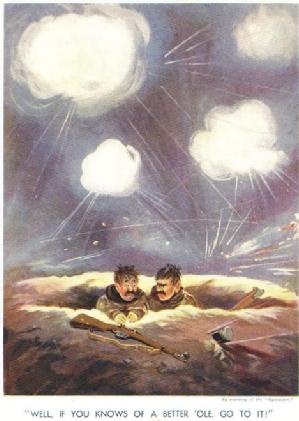

In Bruce Bairnsfather’s celebrated cartoon, two infantrymen of the Great War cower in a foxhole while shells fly overhead. One says to the other: “Well, if you knows of a better ’ole, go to it.” Their passive misery captures much of how the Great War is remembered today. Most wars are rich in tales of agency and decision. Yet many tales of the Great War are told otherwise. A dominant narrative of the Great War tells us that we were passive victims of an irrational disaster: Everything that happened was done to us; we scarcely know by whom.

Perceptions of the Great War continue to resonate in today’s world of international politics and policy. Most obviously, does China’s rise show a parallel with Germany’s a century ago? Will China’s rise, unlike Germany’s, remain peaceful? ‘The analogy [of China today] with Germany before the first world war is striking,’ The Financial Times journalist Gideon Rachman wrote last year. ‘It is, at least, encouraging that the Chinese leadership has made an intense study of the rise of great powers over the ages – and is determined to avoid the mistakes of both Germany and Japan.’

The idea that China’s leaders wish to avoid Germany’s mistakes is encouraging, certainly. But what are the ‘mistakes’, exactly, that they will now seek to avoid? And while much attention has been focused on China’s rise and the German parallel, less has been given to Russia’s decline, which in some ways resembles that of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and with the same disturbing implications: a sprawling, multi-national empire, struggling to manage a fall from past greatness, rising ethnic tensions, and external rivals competing for influence in bordering states – in Russia’s case from the Baltic through Ukraine to the Far East.

The idea that China’s leaders wish to avoid Germany’s mistakes is encouraging. But what ‘mistakes’ will they seek to avoid?

The world can hardly be reassured if we ourselves, social scientists and historians, remain uncertain what mistakes were made and even whether they were mistakes in the first place. The myths of the Great War challenge the skills of both historians and economists. Historians face the challenge of preserving and extending the record and contesting its interpretation – especially when reasonable people differ over the meaning. If anything challenges the economist, it is surely persistence in behaviour that is both costly and apparently futile or self-defeating.

With this in mind, I review four popular narratives relating to the Great War. They represent prevailing but inaccurate views about essential elements of the war: why it started, how it was won, how it was lost, and in what sense it led to the next war.

The myth of an inadvertent war

Interviewed earlier this year at Davos, Japanese premier Shinzo Abe likened China and Japan today to Britain and Germany in 1913 – both in terms of their rivalry and their ties through trade. He noted that a century ago similarly strong trade between Britain and Germany had not prevented strategic tensions leading to the outbreak of conflict. Today, he concluded, any “inadvertent” conflict would be a disaster.

Historians and politicians have focused on moral responsibility for the war. Whom should we blame? When the Great War ended, much discussion on the allied side centred on ‘who was to blame’ and advice to ‘hang the Kaiser’ was widespread. Historians continue to debate the question of moral responsibility.

From a social-science perspective, in contrast, the issue is less moral than empirical: Was the Great War truly an ‘inadvertent’ conflict, one that started when no one was looking? When the actors decided on war, to what extent did they calculate their actions and intend the results? The economist’s standard model of behaviour demands evidence of personal action (rather than anonymous collective drift), based on calculation that looks to the future (rather than only reacting to the present) and that takes others’ calculations into account (that is, action will be met by counter-action).

It is a myth that such calculations were absent from the decision for war. On the contrary the record shows that the war was brought about very largely by design, and those who designed it made realistic calculation of the possible scale, scope, duration, and even outcomes of the war.

The key decisions that launched the Great War were highly calculated with clear foresight of the possible wider costs and consequences

In every country, the decision for war was made by a handful – literally – of people at the apex of each political system. Their councils were ‘saturated with agency’. The cliques themselves were not united, so that there were also waverers in every country including the German, Austrian, and Russian emperors, the German premier Bethmann Holweg, and the British finance minister (later premier) Lloyd George. At crucial moments, however, those who favoured war were able to sway the others.

What ruled the calculation in every country was the national interest as they perceived it. But on what was the ‘national interest’ based? As everywhere, on shared beliefs and values. These began with national identity, in which the well-being of the nation was commonly identified with persistence of the ruling order. They extended to shared values of power, status, honour, and influence, and then to shared beliefs about the forces underlying the distribution of power in the world. Strikingly, the decision makers in every country were subscribers to a virtual world where the negative-sum game of power was being played out, not the positive-sum game of commerce and development. The Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires were in decline. This triggered a struggle for geopolitical advantage.

There is clear evidence that some of the actors had a specific intent to bring about a war. They understood how others would respond and that a wider conflict would probably ensue, and they either took the chance or welcomed it as an opportunity. In Vienna, chief of the general staff Conrad von Hötzendorf and foreign minister Leopold von Berchtold intended war with Serbia in order to assert the integrity of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, knowing that the Russians might intervene and so widen the conflict. In Berlin, chief of the general staff Helmuth von Moltke and war minister Erich von Falkenhayn planned war with Russia before the Russian rearmament would be completed, knowing that this would also entail war with France. To bring war about, they also encouraged each other: when the Germans encouraged the Austrians to make war on Serbia in July 1914, among them were those that expected this would provide the best opportunity to attack France and Russia. Similarly, the Russians and French egged each other on, although the Russians had their eyes on Austria and the French on Germany.

In fact, the key decisions that launched the Great War were highly calculated with clear foresight of the possible wider costs and consequences. There was little overoptimism. The spirit of those who gave the orders is more usefully defined as ‘rational pessimism’: they did not expect victory if they went to war, but they expected less from peace than from gambling on war. The German and Austrian leaders believed their enemies were growing in strength. While recognizing the possibility of defeat, they also feared the future would never favour victory more than the present. This ‘rational pessimism’ turned them into risk-takers.

The failure of deterrence was an immediate cause of the war. A deeper cause was the authoritarian regimes of the Central Powers and Russia, under which a few war advocates could decide the fate of millions in secret.

The myth of needless slaughter

The Great War took place in an era of mass armies. This era began in the 1860s, when the railway technology first enabled the assembly and deployment of multi-million armies, and ended in the 1970s when battlefield nuclear weapons and cruise missiles deprived the same mass armies of their viability.

Attrition was a reality; was it pointless? That idea was founded on two rates of exchange: lives for lives, and lives for territory. Lives for territory: In most battles on the western front until 1918 only a few yards changed hands for thousands or tens of thousands of casualties. Lives for lives: When the Allied armies traded with the enemy, they consistently came off worse. Two things are clear. First British losses rose greatly with the forces deployed. Second, British losses consistently exceeded those of the adversary in the same sector: by nearly two to one in the period before the Somme and still by 1.5 to one after it. At that rate, the Allied policy of attrition was irrational. Did the Allied generals see this?

During the war, however, the solution to attrition presented itself, and the Allies were better able to grasp this solution than the Central Powers

In fact, commanders on both sides made repeated efforts to escape the logic of attrition. The problem was that every attempt at escape seemed to come to nothing. In the category of efforts intended to save lives on the Western front were: the artillery preparations with which Allied commanders preceded major attacks (ineffective more often than not); Churchill’s attack on the underbelly of the Central Powers via the Dardanelles (a costly failure); the Allied blockade of Germany (slow acting at best); and German submarine attacks on Allied and neutral shipping (arguably ineffective and certainly counter-productive in bringing America into the war).

Based on manpower alone, a strategy of attrition was self-defeating: the Allies could have expected to lose the war. Kitchener’s ‘last million’ (men) turned out to come from America, which no one anticipated in 1914. During the war, however, the solution to attrition presented itself, and the Allies were better able to grasp this solution than the Central Powers. The stalemate would be broken not by manpower but by firepower. Additional firepower was supplied by the Allied economies, which were tremendously richer than those of the Central Powers. First to grasp this was Lloyd George, who echoed Kitchener in 1915 by claiming that Britain would raise the ‘last million’ (pounds) that would win the war.

To conclude, in the Great War, despite material advantage, the Allies could not escape the war of attrition. Attrition meant slaughter. Some of this slaughter was the kind of pointless, wasteful killing that happens in every war. The rest of it was the killing demanded in both world wars by mass warfare. Attrition was not only slaughter, however. There was an economic dimension as well as the military one. It was the combined attrition in two dimensions that defeated the Central Powers.

The myth of the food weapon

The belief that Germany was starved into submission by the allied blockade has considerable historic significance. This interpretation was used after the war by Hindenburg and Ludendorff to sustain the their notion that Germany had been defeated not militarily but by a collapse of the home front. It also formed Hitler’s strategic orientation towards food security and colonization of the farmlands to the East. As Hitler remarked in 1939, ‘I need the Ukraine, so that no one is able to starveus again, like in the last war.’

The idea that Germany was defeated by denial of trade would have struck contemporaries as unlikely, since Britain imported 60 per cent of calories for human consumption while Germany imported only 25 per cent at most. Yet three quarters of a million Germans died of hunger and hunger-related causes, while the British population survived relatively unscathed.

In Britain sugar was rationed from the end of 1917 and various meats and fats during 1918. The access of low-income families to food improved somewhat, so there was a degree of equalization. This seems more likely attributable to the high demand for all kinds of labour than to rationing itself. In Germany price ceilings and rationing were introduced in 1916 for bread and flour, meat, fats, and oil. Food rationing supplied only 50-60 percent of required calories, so everyone had to go to unofficial sources to survive. In this setting the wealthy had the advantage.

Decisions made in Berlin are a much better candidate for causes of the German nutritional collapse than those taken in London

One problem for Germany was that she went to war with the very countries that were supplying the bulk of these imports. To this extent no blockade was needed to interrupt trade across no man’s land. The Allies simply stopped trading with Germany.

That Germany’s food imports would be severely reduced was well-anticipated. Pre-war plans for wartime autarky assumed that German farmers would farm more intensively to feed the nation . A bigger problem here was the supply shock from war mobilization, which stripped German farms of young men, horses, and chemicals. Further shocks came from farmers’ incentives. At the same time that battlefronts and blockades cut off food imports across open borders, war mobilization restricted the domestic supply of manufactured goods to the rural market. Although food prices soared, farmers retreated to the inside option of self-sufficiency. When civilian officials stepped in to control prices, the attraction of the inside option only increased.

Of these two shocks, the one from trade affected at most one quarter of Germany’s food supply (less, in fact, because not all trade was suppressed). The shock from mobilization affected the three quarters that was home produced. It is implausible to give priority to the former over the latter. In other words, decisions made in Berlin are a much better candidate for causes of the German nutritional collapse than those taken in London.

The myth of folly at Versailles

In 1920, Keynes strongly criticized the Versailles settlement on two grounds: it violated the terms of the Armistice (which limited German reparations to making good civilian damages arising from the war), and the resulting burden on the German economy was intolerable and would be counterproductive. Like the myth of the food blockade, the idea that Versailles helped lay the foundations for another war 20 years later, is reinforced by the extent to which Nazi leaders campaigned against it to mobilise support. Just this year, the financier and philanthropist George Soros warned that just as the French insistence on reparations had given rise to Hitler, ‘Angela Merkel’s [similar] policies are giving rise to extremist movements in the rest of Europe.’

The burden of German reparations determined in 1921 was certainly heavy and probably unwisely so. The evidence is plain to see in the better outcome of 1945, when the victors based retribution on evidence of personal culpability, not collective responsibility. Still, the mistakes of 1919 to 1921 should be kept in perspective.

If the economic implications of the Treaty have been oversold, the same is true of its political consequences

The role of reparations can be seen through the prism of hyperinflation. There was a war of attrition between the Allied and German governments over the distribution of post-war burdens, and this is part of the story of the German 1923 hyperinflation. But reparations were not a necessary condition for this, because there were many hyperinflations at this time across central and Eastern Europe in countries that did not face reparations but did suffer from domestic wars of attrition over the burdens of post-war adjustment. Rather, the German war of attrition was unusual only because external bondholders played such a salient role.

Another aspect of the Treaty provisions also came into play. Measures limiting German rearmament gave Germany fiscal breathing space. Restrictions on the size and equipment of Germany’s armed forces reduced the burden of military spending.

If the economic implications of the Treaty have been oversold, the same is true of its political consequences. The electoral history of the Weimar Republic shows a brief period of radicalization in the aftermath of the Versailles Treat. After that, the moderate parties of the centre and left regained strength with every election. During the period when reparations were heaviest, political moderation had a firm grip. It was not until the hammer blow of the Great Depression that conditions were laid for violent polarization and the breakthrough of the radical right to national significance and power.

Conclusions

The history of the Great War has implications for today. Secretive, authoritarian regimes become dangerous when they fear the future. Deterrence matters. Trench warfare was terrible, but not uniquely so. It is total war that is terrible and total war cannot be done cheaply. The blockade of Germany provides one more case study of economic sanctions that have been less effective than believed by both perpetrators and victims. The treaty of Versailles, however unwise, was not a slow fuse for another war. It led to a new war of attrition between government and bondholders of the kind that typically ends peacefully, and would have done so in this case without the Great Depression.

comments powered by Disqus