2013(1) - Stebek

Contents

- Introduction

- Development and enhanced living standards envisaged under Ethiopian law and development strategies

- National competitiveness and productivity

- Improved living standards

- The demographic challenge in enhancing living standards and its pressure on the environment

- The Millenium Development Goal One to eradicate extreme poverty

- Between statistical figures and facts on the ground

- Concluding remarks

- References

‘Development’ and Improved Living Standards

The Need to Harmonize the Objectives of Ethiopian Investment Law

Elias N. Stebek

LL.B, LL.M (Addis Ababa University), PhD (University of Warwick)

Dean, St. Mary’s University College School of Graduate Studies

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Abstract

Ethiopia’s Investment Proclamation (i.e. Proclamation No. 769/2012) states that strengthening domestic production capacity which leads to accelerated economic development and improved living standards of the Ethiopian people are the objectives of ‘the encouragement and expansion of investment.’ Moreover, the 1995 Ethiopian Constitution guarantees ‘the right to improved living standards and to sustainable development.’ The article briefly addresses the core elements of these objectives, i.e. ‘the enhancement of domestic production capacity’, ‘development’ and ‘improved living standards.’ I argue that there is tension between these triple objectives as long as ‘economic development’ tends to merely focus on rise in production rather than the enhancement of domestic production capacity and without due focus to the enhancement of the living standards and the quality of life of the vast majority of the population at the grassroots.

This is a refereed article published on: 31st July 2013

Citation: Stebek, E.N. (2013) ‘Development and Improved Living Standards: The Need to Harmonize the Objectives of Ethiopian Investment Law’, 2013(1) Law, Social Justice & Global Development Journal (LGD). http://www.go.warwick.ac.uk/elj/lgd/2013_1/stebek

Keywords

Investment promotion, domestic production capacity, development, improved living standards, demographic transitions.

1. Introduction

Investment toward the production of goods and services presupposes saving or mobilization of capital to generate profit, to obtain interest or to benefit from the appreciation of value. In effect, it simultaneously serves the self-interest of investors and the common good. Investment involves economic activities that usually bring about supply of goods or services to society, financial benefits to the owner/s, employment opportunities, technological spillovers, tax revenue, foreign exchange earnings, export promotion, import substitution, and other multifaceted benefits. Ultimately, the benefit accrued from every investment is an element of the overall social benefit which takes the form of economic and social development. The objectives of investment promotion in Ethiopia’s Investment Proclamation thus envisage not only statistical growth in the production of goods and services but also the steady enhancement of domestic production capacity and corresponding positive changes in the standards of living of the majority at the grassroots.

This article briefly addresses the objectives of investment promotion in Ethiopia embodied in the Preamble and Article 5 of Ethiopia’s Investment Proclamation No. 769/2012, namely strengthening domestic production capacity in Ethiopia to bring about ‘economic development’ and ‘improved living standards’ of people. To this end, it highlights the specific objectives of investment promotion in Ethiopia and the embodiment of the economic, social and environmental pillars of sustainable development in the Ethiopian Constitution after which a brief discussion is made on national competitiveness and productivity, the notion of standards of living, the demographic challenge in enhancing living standards and its pressure on the environment, the Millennium Development Goal to eradicate extreme poverty, and the tensions that permeate the gaps between Ethiopia’s GDP/HDI growth figures vis-à-vis the standards of living of the majority at the grassroots.

2. Development and enhanced living standards envisaged under Ethiopian law and development strategies

Article 43(1) of the Ethiopian Constitution stipulates that ‘[t]he People of Ethiopia as a whole, and each Nation, Nationality and People in Ethiopia in particular have the right to improved living standards and to sustainable development.’ In conformity with this constitutional provision, the first paragraph in the Preamble of Ethiopia’s Investment Proclamation[1] states that ‘… the encouragement and promotion of investment, especially in the manufacturing sector, has become necessary so as to strengthen the domestic production capacity and thereby accelerate the economic development of the country and improve the living standards of its peoples.’

According to Article 5 of the Investment Proclamation ‘the objectives of the investment policy of Ethiopia are designed to improve the living standards of the peoples of Ethiopia through the realization of sustainable economic and social development.’ Sub-Articles 1 to 8 of the provision state that the specific objectives of Ethiopia’s investment policy are to (1) ‘accelerate economic development’; (2) ‘exploit and develop the immense natural resources of the country’; (3) ‘develop the domestic market through the growth of production, productivity and services’; (4) ‘increase foreign exchange earnings by encouraging expansion –in volume and variety and quality – of the country’s export products and services as well as to save foreign exchange through production of import substituting products locally’; (5) ‘encourage balanced development and integrated economic activity among the regions and to strengthen the inter-sectoral linkages of the economy’; (6) ‘enhance the role of the private sector’ in accelerated economic development’; (7) ‘enable foreign investment play its proper role in the country’s economic development’; and (8) ‘create ample employment opportunities for Ethiopians and to advance the transfer of technology required for the development of the country.’

Although Article 5 of Ethiopia’s Investment Proclamation uses the terms ‘sustainable economic and social development’, the specific objectives do not reflect the integration of the three interdependent pillars of sustainable development which ‘reconcile the ecological, social and economic dimensions of development, now and into the future’.[2] The incidental reference made to the environment in Article 5(2) is indeed inadequate even if envisages not only the exploitation of natural resources, but also their simultaneous development. Most of the stipulations under Article 5 thus clearly fall under one of the pillars of sustainable development, i.e. economic development. These provisions could have at least made general reference to the social and environmental concerns.

They thus fall short of both the ‘weaker’ model of sustainable development ‘whose aim is to integrate capitalist growth with environmental concerns’[3] and the ‘strong’ version which ‘requires that political and economic policies be geared to maintaining the productive capacity of environmental assets (whether renewable or depletable)’.[4] While the former considers economic development as a precondition of environmental protection, the latter on the contrary asserts ‘that environmental protection is a precondition of economic development’.[5]

The tension between the pillars of sustainable development is usually resolved in favour of economic actors who may either use the phrase as a façade for the ‘growth first’ paradigm or as a public relation medium. This is particularly so, when the institutions in charge of enforcing environmental compliance standards are weak. The mere embodiment of legal provisions that require a balance in the three dimensions of sustainable development cannot thus ensure the applicability of the notion. As Nayar notes, the notion of sustainable development can be maneuvered ‘depending on one’s inclination’.[6] He observes that the concept of sustainable development ‘does not articulate a well-defined strategy for action’ and ‘remains an accepted philosophical approach but in a vacuum’.[7] The strength of the concept thus lies not in its mere embodiment in laws as a concept or principle but in its integration with enforceable specific laws. The constitutional provisions on sustainable development should thus be used as a norm of ‘integration’ that facilitates a ‘balance and reconciliation between conflicting legal norms relating to environmental protection, social justice and economic development’.[8]

Articles 89 to 92 of the FDRE Constitution state the economic, social, cultural and environmental objectives that are required to be the pursuits of the Ethiopian Government at federal and state levels. Article 89 titled ‘Economic Objectives’ lists down the duty of the Government (federal and state) to: (1) formulate policies that ensure ‘all Ethiopians to benefit from the country’s legacy of intellectual and material resources’; (2) ‘ensure that all Ethiopians get equal opportunity to improve their economic condition and to promote equitable distribution of wealth among them’; (3) ‘take measures to avert any natural and man-made disasters, and, in the event of disasters, to provide timely assistance to the victims’; (4) ‘provide special assistance to Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples least advantaged in economic and social development’; (5) ‘to hold, on behalf of the People, land and other natural resources and to deploy them for their common benefit and development’; (6) ‘promote the participation of the People in the formulation of national development policies and programmes’ and also ‘support the initiatives of the People in their development endeavors’; (7) ‘ensure the participation of women in equality with men in all economic and social development endeavors’; and (8) ‘endeavor to protect and promote the health, welfare and living standards of the working population of the country.’

Some of the objectives stated under Article 89 such as health can also be considered as social objectives. Articles 90 and 91 embody the social and cultural objectives embodied under the Constitution. Article 90 states the Government’s duty to provide all Ethiopians (to the extent resources permit) ‘access to public health and education, clean water, housing, food and social security’[9] and provide education ‘in a manner that is free from any religious influence, political partisanship or cultural prejudices’.[10] The cultural objectives embodied under Article 91 of the Constitution state the government’s duty to support ‘the growth and enrichment of cultures and traditions that are compatible with fundamental rights, human dignity, democratic norms and ideals, and the provisions of the Constitution’ [11] and also support (to the extent resources permit) ‘the development of the arts, science and technology’. [12]

Article 91(2) further entrusts the Government and all Ethiopian citizens with the duty ‘to protect the country’s natural endowment, historical sites and objects.’ These duties that are expected of the Government include both duties of result and duties of diligence. In the case of certain rights that bear qualifying phrases such as ‘shall endeavour’ and ‘to the extent that resources permit’ the rights can only be progressively realized. The environmental objectives stipulated under Article 92 of the Constitution include such duties.

By virtue of Article 85(1) of the Constitution, ‘[a]ny organ of Government shall, in the implementation of the Constitution, other laws and public policies, be guided by the principles and objectives specified under [Articles 85 to 92 of the Constitution].’ Article 43(2) of the Constitution which (as highlighted above) ensures ‘the right to improved living standards and to sustainable development’ in conjunction with the stipulations enshrined in Articles 85 to 92 clearly show that the economic, social and environmental dimensions of development are required to be considered in all pursuits of investment and development.

Ethiopia has gone through various development strategies in the course of implementing these objectives. The Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction Programme (SDPRP) for the period 2002/03-2004/05 became the basis for the Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP), during the period (2005/6-2009/10). Ethiopia’s Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) is a five-year (2010-2015) plan which, inter alia has the objectives[13] of maintaining ‘at least an average real GDP growth rate of 11%,’ meeting the Millennium Development goals and ensuring growth sustainability by realizing all the objectives enshrined in the GTP ‘within stable macroeconomic framework.’ The tasks envisaged in the GTP are linked with the Millennium Development Goals and details with regard to objectives, output, indicators, baseline, annual targets, implementation agency, and means of verification are stated therein. The pillar strategies toward the attainment of the objectives include the sustenance of ‘faster and equitable economic growth, maintaining agriculture as a major source of economic growth, creating favorable conditions for the industry to play key role in the economy’, infrastructure, social development, good governance, women and youth empowerment.

The Growth and Transformation Plan (Volume 2, Policy Matrix) [14] embodies sixteen tables most of which deal with economic growth.[15] Yet, the balance that is envisaged between the economic, social and environmental aspects of sustainable development in the Ethiopian Constitution and the Millennium Development Goals are expected to underpin the implementation of the Growth and Transformation Plan. To this end, Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy states the need for caution against the conventional economic growth paradigm:

Conventional economic growth could lead to ... challenges … such as depleting the very natural resources that Ethiopia’s economic development is based on, locking it into outdated technologies, and forcing it to spend an ever-larger share of GDP on fossil fuel imports. In addition to lower public health due to diseases related to indoor air pollution, further forest degradation and soil erosion would also occur, diminishing food security and destroying sources of drinking water.[16]

3. National competitiveness and productivity

The objectives of investment promotion in Ethiopia, i.e., ‘domestic production capacity’, ‘development’ and ‘improved standards of living’ involve meanings and dimensions that are deeper than their simplistic usage in day to day parlance. A caveat is thus necessary to pay attention to the notions of ‘economic development’ that emanates from the enhancement of domestic production capacity and that can bring about ‘improved standards of living.’ Production capacity can be defined as the ‘[v]olume of products that can be generated by a production plant or enterprise in a given period by using current resources’.[17] At the national level, domestic production capacity is related with the competitiveness of an economy in producing goods and services in a given time and under available resources. Enhancement in economic development and standards of living are inconceivable without the enhancement of domestic production capacity.

Sulzenko and Kalwarowsky[18] note the crucial role of labor productivity and total factor productivity in enhancing standards of living. They criticize the tendency ‘to equate a higher standard of living with a higher level of consumption’ and state that ‘the key to long-term prosperity is productivity’ because increase in ‘productivity is what makes increased consumption possible.’ They further state that labor productivity ‘measures the value of goods and services produced per unit of labor time’ and this refers to ‘the value of goods and services produced in a given period of time, divided by the amount of labor used to produce them’. According to Sulzenko and Kalwarowsky, ‘[t]otal factor productivity (or multi-factor productivity) looks at all three factors of production: labor, materials, and capital’; and it measures ‘the efficiency with which people, capital, resources, and ideas are combined in the economy’.[19]

Growth in production can be attributed to ‘increases in factor inputs’ such as the expansion of farmland or it may be attributed to ‘increases in output per unit of input (productivity)’.[20] The former targets at frontier expansion, whereas the latter relies on productivity and competitiveness. Setting aside ‘extractive’ investment projects that primarily aim at the extraction of environmental assets, value adding investment projects choose their investment destinations based on national competitiveness and productivity. Competitiveness can be defined as ‘the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country’.[21]

The level of productivity, in turn, sets the level of prosperity that can be earned by an economy. The productivity level also determines the rates of return obtained by investments in an economy, which in turn are the fundamental drivers of its growth rates. In other words, a more competitive economy is one that is likely to grow faster over time.[22]

The World Economic Forum identifies the following 12 pillars[23] of national competitiveness:

Basic requirements: Key for factor driven economies

1. Institutions

3. Macroeconomic environment

2. Infrastructure

4. Health and primary education

Efficiency enhancers: Key for efficiency-driven economies

5. Higher education & training

8. Financial market development

6. Goods market efficiency

9. Technological readiness

7. Labor market efficiency

10. Market size

Innovation and sophistication factors: Key for innovation-driven economies

11. Business sophistication

12. Innovation.

Although these factors are interrelated, the report relates the role of these pillars particularly with the stage of the development of the host economy and nature of the investment. In factor-driven investments, ‘countries compete based on their factor endowments—primarily unskilled labor and natural resources’ and potential investors ‘compete on the basis of price and sell basic products or commodities, with their low productivity reflected in low wages’.[24] In investments that are factor-driven, a nation’s competitiveness ‘primarily hinges on well-functioning public and private institutions (pillar 1), a well-developed infrastructure (pillar 2), a stable macroeconomic environment (pillar 3), and a healthy workforce that has received at least basic education (pillar 4)’.[25] The 2012 Global Competitiveness Report explains the twelve pillars in national competitiveness, among which the key four pillars that determine competitiveness in factor-driven investments are defined as follows:[26]

a) Institutions (… ‘determined by the legal and administrative framework within which individuals, firms, and governments interact to generate wealth’ including inter alia the nature of property rights, markets, excessive bureaucracy and red tape, overregulation, corruption, dishonesty in dealing with public contracts, lack of transparency and trustworthiness, and political dependence of the judicial system);

b) Infrastructure (modes of transport, ‘electricity supplies that are free of interruptions and shortages so that businesses and factories can work unimpeded’, ‘solid and extensive telecommunications network allows for a rapid and free flow of information, which increases overall economic efficiency’ …);

c) Macroeconomic environment (level of interest payments on its past debts and running fiscal deficits, inflation rates, etc);

d) Health and primary education (the level of health services and primary education towards a healthy and productive workforce).

4. Improved living standards

Standard of living is considered as ‘not only the ownership of consumer goods, but also aspects of living that cannot be purchased or are not under an individual's direct control – for instance, environmental quality and services provided by the government’.[27] Such wider definitions of ‘standard of living’ do not undermine the importance of material comfort as one of the core elements in living standards, but include other elements as well. Even if value systems influence the conception of ‘material comfort’, Pigou argues that there should be ‘a minimum standard in real income’ that should be established by governments and below which no citizen should fall.[28] Pigou’s notion of minimum objective standards requires the satisfaction of minimum material well-being which can be ascertained and measured.

It must be conceived, not as a subjective minimum of satisfaction, but as an objective minimum of conditions. The conditions, too, must be conditions, not in respect of one aspect of life only, but in general. Thus the minimum includes some defined quantity and quality of house accommodation, of medical care, of education, of food, of leisure, of the apparatus of sanitary convenience and safety where work is carried on, and so on.[29]

Amartya Sen’s conception of standards of living and wellbeing is broader than the one propounded by Pigou. He relates standards of living with ‘quality of living.’ He notes that “[y]ou could be well off, without being well. You could be well, without being able to lead the life you wanted. You could have got the life you wanted, without being happy. .... You could have a good deal of freedom, without achieving much.[30] Sen notes three elements of standards of living which he refers to as opulence, functionings and capabilities. He appreciates Pigou’s contribution to the discourse on standards of living and, in principle, agrees to Pigou’s views on the role of ‘real income’ in living standards. But Sen believes that Pigou did not go far enough in his analysis regarding the minimum standard [31] that can most effectively promote economic welfare.

Consider two persons A and B. Both are quite poor, but B is poorer. A has a higher income and succeeds in particular in buying more food and consuming more of it. But A also has a higher metabolic rate and some parasitic disease, so that despite his higher food consumption, he is in fact more undernourished and debilitated than B is. Now the question: Who has the higher standard of living of the two? ... A may be richer and more opulent, but it cannot really be said that he has the higher standard of living of the two, since he is quite clearly more undernourished and more debilitated. The standard of living is not a standard of opulence, even though it is inter alia influenced by opulence. It must be directly a matter of the life one leads rather than of the resources and means one has to lead a life. The movement in the objectivist direction away from utility may be just right, but opulence is not the right place to settle down.[32]

Under current Ethiopian realities, we can think of two persons working in the same place with different lifestyles. ‘A’ may be a khat (chat) addict who spends about half of his monthly income on khat (chat) and other alcoholic drinks for lulukecha[33] while his friend ‘B’ does not incur such expenses. The living standard of ‘B’ is, ceteri paribus, higher than ‘A’ even if the monthly income of the former is half the salary of the latter, because in addition to the expenses incurred, the impact of such addiction on health and overall emotional tranquility adversely affects A’s standard of living.

This indicates the need to revisit the current laissez faire policy trend in the meteorically rising khat production and circulation, which at their face value seem to generate revenue at farm level and in foreign exchange earnings. The adverse impact of this wave includes primarily, its negative role in food security (due to the diversion of crop yielding farms to khat production) and the resultant rise in food prices, and secondly, the harm to the health, monthly budget and overall emotional and mental wellbeing of citizens. As Sen indicates, “[b]eing psychologically well-adjusted may not be a ‘material’ functioning, but it is hard to claim that that achievement is of no intrinsic importance to one's standard of living”. Sen recalls Marx’s criticism against ‘commodity fetishism’ and underlines the need to see beyond the role of commodities and material possessions:

The market values commodities, and our success in the material world is often judged by our opulence, but despite that, commodities are no more than means to other ends. Ultimately, the focus has to be on what life we lead and what we can or cannot do, can or cannot be. ...[T]he various living conditions we can or cannot achieve [are] our “functionings,” and our ability to achieve them [are] our ‘capabilities.’ [34] The main point here is that the standard of living is really a matter of functionings and capabilities, [35] and not a matter directly of opulence, commodities, or utilities.

Sen states that ‘some of the same capabilities (relevant for a ‘minimum’ level of living) require more real income and opulence in the form of commodity possession in a richer society than in poorer ones.’ After noting the relevance of the satisfaction of basic needs in standards of living, he argues that these ‘basic needs in the form of commodity requirements are instrumentally (rather than intrinsically) important’, because ‘[t]he main issue is the goodness of the life that one can lead.’ He observes the variation in our ‘needs of commodities for any specified achievement of living conditions’ that greatly depend on ‘various physiological, social, cultural, and other contingent features.’ He notes that ‘the value of the living standard lies in the living and not in the possessing of commodities, which has derivative and varying relevance.’

Sen states Dewey’s views on the distinction between a person's overall achievements (whatever he wishes to achieve as an ‘agent’), and his personal well-being,[36] and compares the notions of agency achievement personal wellbeing, and the standard of living.[37]

The distinction between agency achievement and personal well-being arises from the fact that a person may have objectives other than personal well-being. If, for example, a person fights successfully for a cause, making a great personal sacrifice (even perhaps giving one's life for it), then this may be a great agency achievement without being a corresponding achievement of personal well-being.

The motivation for actions may, according to Sen, arise [not only from self-interest but also] from ‘sympathy’ or ‘commitment’. Pursuits that emanate from sympathy can enhance the wellbeing of the person who does an act, while the agent may not personally benefit from commitments. Sen cites the example of helping another person to reduce the latter’s misery, which ‘may have the net effect of making one feel – and indeed be - better off’.[38] In cases of commitment, however, ‘a person decides to do a thing (e.g., being helpful to another) despite its not being, in the net, beneficial to the agent himself.’ This should be distinguished from the usage of the word ‘commitment’ for a job, etc which apparently contributes to the person’s satisfaction and wellbeing.

At the risk of over-simplification, it may be said that we move from agency-achievement to personal wellbeing by narrowing the focus of attention through ignoring ‘commitments,’ and we move from personal wellbeing to the standard of living by further narrowing the focus through ignoring ‘sympathies’ (and of course ‘antipathies,’ and other influences on one’s well-being from outside one’s own life). Thus narrowed, personal well-being related to one’s own life will reflect one’s standard of living.[39]

In light of the discussion hereabove, it is to be noted that ‘the successes and failures in the standard of living are matters of living conditions and not of the gross picture of relative opulence that the GNP tries to capture in one real number’. [40]

5. The demographic challenge in enhancing living standards and its pressure on the environment

Since the 1970s there is an increasing awareness about the relationship and ‘interdependence between economic and demographic variables and the determinants of the rural-urban migration’.[41] Low-income economies pay due attention to population policy not because population growth is intrinsically a vice, but because it ought to correspond with the pace of economic development so that every citizen can lead a decent living.

Hayami and Godo contrast population growth that occurred during the economic growth of today’s advanced economies vis-à-vis the current population growth in low income economies. First, the speed of the latter is faster than the one which occurred in the early development phase of advanced economies.[42] Secondly, population growth in the advanced economies ‘was essentially an endogenous phenomenon induced by accelerated economic growth,’ increased employment and income. On the contrary, today’s population growth in low-income economies ‘has largely been exogenous in nature’ mainly owing to ‘importation of health and medical technologies from advanced economies’.[43]Population growth unmatched by a higher pace of economic development means that ‘there is less to go around per person, so that per capita income is depressed’.[44] In the case of endogenously induced population growth which is driven by economic development, however, ‘[m]ore people not only consume more, they produce more as well. The net effect must depend on whether the gain in production is outweighed by the increase in consumption’.[45]

For instance, soil degradation ‘during the five decades after 1945 amounted to about two billion hectares or about 17 per cent of total vegetative area in the world’[46] out of which about 80% occurred in Africa.[47] The factors for the degradation are attributed to deforestation (about 30%), overexploitation for fuel wood, fodder, etc. (about 7%), overgrazing (about 35%), agriculture (about 28%) and industrialization (about 1%).[48] Although commercial logging and degradation owing to modern agriculture such as excess of irrigation water and chemicals were identified as factors in the degradation process, ‘by far the largest cause is identified as the exploitation of natural resources by the poverty-driven population’.[49]

Hyami and Godo consider pauperization of the rural population due to population pressure as a ‘major factor underlying environmental degradation in developing economies’ and suggest ‘increasing employment and income by improving the productivity of the limited land already in use’.[50] They also underline the need for ‘shifting from traditional resource-based to modern science-based agriculture’ and regulating the ‘cultivation of fragile land for subsistence in hills and mountains’.[51] This in the Ethiopian context requires focus on the increase in productivity per farm site rather than rise in production which mainly arises from expansion of farmland frontiers, and which in reality represents decline in natural capital because such frontier expansion brings about decline in forests, wildlife, biodiversity and ecosystem sustainability.

... [I]n many parts of the world, pressure of population on resources is already so great or threatens to become so great that, however we might define an optimum population, there would be a general consensus that the optimum was exceeded. In such countries heavy population pressure is already an important cause of a low standard of living. ... But in many of these countries heavy population pressure leads to one or other or both of two further evils- to heavy unemployment and/or to great inequalities in the distribution of income.[52]

Meade states three factors, i.e. sparse population, technical progress and capital accumulation as ‘sets of forces which may prevent the pressure of a larger population on a given limited amount of natural resources from causing a fall in output per head’.[53] In the absence or inadequacy of these factors, rise in population, i.e. ‘increase in labour alone’ will not, according to Meade, cause increase in total output[54] thereby adversely affecting standards of living. Ester Boserup, however, (in some circumstances) regards population growth as a stimulus rather than impediment to economic change[55] because she believes that it can stimulate the enhancement of agricultural output, raising production per unit of land, technology and labor.[56] This is based on the assumption that the rural population resorts to change in technical progress and productivity rather than putting pressure on forests, hills and mountains by using the same traditional technology and subsistence agriculture.

In the setting which Boserup observed (i.e. India), private landowners can effectively defend against rural encroachments for farming and grazing, thereby rendering it impossible for farmers to make ends meet unless they raise outputs per unit of land, technology and labour. On the contrary, the incentive of land management on smallholder farms is very weak in Ethiopia mainly owing to the land tenure regime. A study shows that ‘Ethiopian farmers are less likely to plant trees and build terraces to protect against erosion – and more likely to increase use of fertilizer and herbicides – if their rights to land are insecure’.[57] Moreover, public ownership of land that is not fully protected from the adverse effects of de facto open access is susceptible to encroachments. Rural farmers who face pressures of population growth will thus, under the Ethiopian context, be tempted to encroach upon publicly owned lands, clear state forests and overuse fertilizes unless there is land security that can create sense of ownership which naturally entails a strong motivation for soil preservation and resource protection from illegal intrusion.

LeBel notes that ‘as long as population is increasing, investment in renewable resources must be made at rates that generate at least a constant stock per capita’.[58] This ‘requires not only incentives to rural producers, but also creating a property rights framework that provides adjusted market valuation of biodiversity at the genetic, species, and community levels’. [59] He duly suggests that there should be ‘incentives to enhance both biodiversity and natural resource productivity’ and that ‘property rights initiatives must be grounded as closely as possible to those who most directly manage an economy’s stock of natural resources’.[60]

6. The Millennium Development Goal One to eradicate extreme poverty

The UN Millennium Development (MDG) Goals, agreed upon by world leaders at the Millennium Summit (2000), mark a breakthrough in embracing a wider conception of development and in formulating goals, targets and indicators far beyond GDP figures. The Millennium Declaration was made by 147 heads of State and Government and 191 nations who became signatories to its adoption and implementation.[61] ‘The MDGs have set quantitative targets for the reduction of poverty’ which envisage fast and sustained growth in real income of the poor, improvements in health, education, gender equality, the environment and other dimensions of human well-being’.[62] The eight goals[63] envisage the eradication of extreme poverty and hunger by 2015 (Goal 1), the achievement of universal primary education by 2015 (Goal 2), the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of women (Goal 3), reduction of child mortality (Goal 4), improved maternal health (Goal 5), combating HIV/AIDs, malaria and other diseases (Goal 6), ensuring environmental sustainability (Goal 7), and developing a global partnership for development (Goal 8).

These goals have twenty one specific targets and sixty indicators that are meant to ‘monitor the achievements of goals and targets’.[64] For example, Goal One of the Millennium Development Goals[65] has three targets, i.e. to (1) ‘halve between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than one dollar a day’; (2) ‘achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all, including women and young people’; and (3) ‘halve between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger.’ The indicators that monitor progress regarding the first target under MDG One are the proportion of population below $1 (PPP) per day, poverty gap ratio, and the share of the poorest quintile in national consumption.

The MDGs are expected to be perceived as holistic approaches to development because achievements in economic growth under weak social and environmental compliance standards are unsustainable. Likewise, achievements in a certain aspect of social wellbeing which, for example, may bring about decline in mortality rates, for example, without a corresponding achievement in economic development, women empowerment, family planning, etc. can further deepen the demographic challenge in the enhancement of standards of living and environmental sustainability. The success of countries, including Ethiopia, can thus be primarily evaluated on their levels of integrated achievement in all the eight MDGs in addition to the efforts made and the successes attained in each goal.

The UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) which was held in June 2012 has ‘decided to launch a process to develop a set of Sustainable Development Goals which will build upon the Millennium Development Goals and converge with the post 2015 development agenda’.[66] The conference has also adopted green economy policies. It was decided to establish an ‘inclusive and transparent intergovernmental process open to all stakeholders, with a view to developing global sustainable development goals to be agreed by the General Assembly’.”[67] The Post-2015 development agenda is expected to build upon the Millennium Development Goals and embody balanced treatment of all the dimensions of development including enablers such as issues of peace, security, institutions and governance in the absence and inadequacy of which pursuits of development are futile.

7. Between statistical figures and facts on the ground

Since the 1930s the Gross National Product and Gross National Income per capita were the prime indicators for economic development, until they were replaced by other indicators such as the Human Development Index, particularly since the 1990s. As far back as 1968, Robert Kennedy had criticized obsessions with numbers and statistical figures in quantifying ‘development’:

... Gross National Product counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage.

It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl.

It counts napalm and counts nuclear warheads and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our cities. It counts Whitman's rifle and Speck's knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children.

Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials.

It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. ...[68]

Although the Human Development Index is a relatively better tool than GDP in measuring development, it shares certain features of the latter in its obsessions with numbers and statistics that conceal social facts at the grassroots. As an Amharic saying goes ‘hodin begomen bidelilut, gulbet bedaget yilegimal’. It means “if you deceive your stomach while having your meal, your muscles will refuse to take you up the hill”.[69] The same holds true with regard to misleading statistical figures. Carr’s observation in this regard reads ‘[w]hen you are standing with a farmer in his field of failing corn, it is nearly impossible to tell him his experience is not real …’.[70] To use Carr’s words, the issue then becomes ‘whether governments, development agencies, and international organizations will try to see what is happening on the ground in communities around the world and deal with that reality, or continue to live in their self-imposed echo chamber’.[71]

Gross Domestic Product and Gross National Income per capita clearly fail to take various factors such as distribution of wealth, subsistence production, non-monetized goods, services and amenities into account. Even if the Human Development Index rectifies some of the shortcomings in the GDP measurement, it shares certain weaknesses with its predecessor. Primarily, it creates pressure on score sheets rather than real achievements. It tends to focus on statistical figures on school coverage, health centres, etc. rather than quality thresholds and standards in the services provided. Ultimately, this creates institutional degeneration and professional mediocrity which makes it difficult for a county to nurture and steadily develop in technology and innovation driven competitiveness. There is thus a tension between pursuits of accelerated ‘economic growth’ which nurtures the quest to report steadily rising figures of achievement vis-à-vis the actual level of domestic production capabilities and competitiveness that should have been the foundation for development and improved standards of living as envisaged in Ethiopia’s Investment Proclamation.

The second tension that can be observed between the triple objectives of Ethiopia’s investment law relates to the pursuits of countries to compare themselves with other countries and with their earlier state of performance rather than objective standards of achievement. Such rush to score points in the rat race against other countries and in comparison to one’s own records, not only can lead to number-fetishism, but also to the neglect of natural assets and non-monetizable endowments which ultimately would adversely affect development, rising standards of living and the quality of life.

Thirdly, there exists a tension between statistical figures of performance in ‘development’ vis-à-vis the actual standards of living and the quality of life of the majority. This can be attributed to temptations on the part of regulatory offices to report statistical ‘achievements’ delinked from quality, standards and benchmarks. This again emanates from ‘praise and blame’ on the basis of ‘statistics’ alienated from insights into the bigger picture. For example, inadequate inflation adjustments and other factors can lead to wrong computations, claims and conclusions. This can explain the reason why visible changes are not seen in Ethiopia’s overall ranking in the global Human Development Index and most importantly in the standards of living for the majority at the grassroots while its achievements in most of HDI indicators show impressive achievements.

The Human Development Index, inter alia, combines three indicators of quality of life, namely: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. In the 2012 Human Development Report (released by UNDP in March 2013), Ethiopia’s rank in the Human Development Index is 173 out of 187 countries.

Ethiopia’s HDI value has remarkably increased from 0.275 in 2000 to 0.396 in 2012, ‘an increase of 44 % or average annual increase of about 3.1%,’ according to the UNDP ….

However, the average HDI for low human development countries stands at 0.466, well above that of Ethiopia’s at 0.396. The Sub-Saharan Africa average HDI which is 0.475 is also above Ethiopia’s. This shows that Ethiopia is not well positioned even

among the worst performers including the Sub-Saharan African countries. … A comparison with other countries at similar level in many other indexes reveals that Ethiopia’s improving HDI stands at a worrisome trajectory and is good only when it is compared to its own figures in the past. … [72]

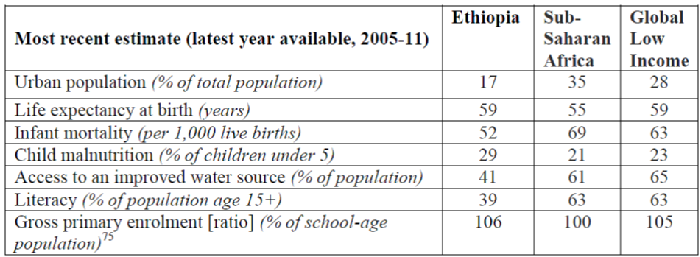

In spite of such HDI achievements Ethiopia’s poverty percentage of population below national poverty line is 30%.[73] The following figures show the level of Ethiopia’s performance in comparison with the Sub-Saharan Average and the global low-minimum average:[74]

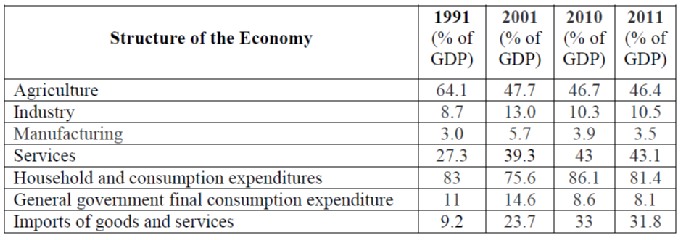

The following data[76] for the two decades between the years 1991 to 2011 shows the structure of Ethiopia’s economy with regard to the share of agriculture, industry and services. It further shows that 81.4 of Ethiopia’s GNP goes to household and consumption expenditures and indicates the steady rise in the percentage of the value of imports which was 31.8% of GNP in 2011 as compared to 9.2% and 23.7% in 1991 and 2001 respectively.

The (1991-2011) two-decade data for Balance of Payments[77] inter alia shows the rise in the value of exports and imports, and the gaps in balance of payments. The value of exports of goods and services in the years 1991, 2001 and 2011 was USD 543 million, 979 million and 4,293 million respectively. During the same period, the value of imports of goods and services was USD 1,226 million, 1,934 million and 10,594 million respectively. It is also to be noted that the conversion rate of Ethiopian Birr to USD was respectively Birr 2.1, Birr 8.5 and 16.9 per US dollar during the years 1991, 2001 and 2011.

8. Concluding Remarks

The words ‘investment, investor, etc.’ are currently being overused to the extent that the essence and features of the concept of investment run the risk of being misconceived. The core objectives of investment promotion embodied in the preamble and Article 5 of Ethiopia’s Investment Proclamation can thus be taken into account as a safeguard against misconceptions in the day-to-day usage of the term ‘investment’ promotion.

Ethiopian Investment Law expressly articulates three objectives: strengthening domestic production capacity, ‘accelerated economic development’ and ‘rising standards of living’. The various incentive schemes toward investment promotion presuppose that every investment project positively contributes towards these objectives. While the first objective of strengthening domestic production capacity is the foundation from which economic development is expected to spring from, the third objective of rising standards of living is envisaged as the outcome of economic development.

The tension between the quest for accelerated economic growth and the need to enhance domestic production capacity is expected to be addressed by giving primacy to the latter because it is envisaged by Ethiopia’s Investment Proclamation as the foundation for the former. Moreover, the tension between the statistical figures in economic growth and the facts on the ground with regard to standards of living can be addressed only through realistic and participatory sustainable development pursuits because the experience of various countries has proven that quick-fixes and mere good intentions to accelerated economic development and rising standards of living usually fail, in the absence of factors (such as institutional capabilities) that determine productivity and competitiveness. As highlighted in Section 3 above, competitiveness refers to ‘the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country’.[78]

Institutions and good governance have always been sine qua non conditions for effective developmental pursuits and rising standards of living. Even if highly elevated levels of institutional capabilities presuppose advanced stages in economic development, lack of the basic thresholds in institutional capabilities hamper development. In the absence of such basic thresholds, mere endowment with abundant natural resources (as experienced in various African countries) merely creates what is known as the ‘resource curse’ as the rent and interest gathered from natural capital are misappropriated by a portion of the bureaucratic and ‘business’ elite in countries where corruption is widespread. Nor is global integration the magical cure, because the realization of win-win economic and social benefits are directly proportional to the level of endogenous institutional capabilities and good governance.

Throughout the preceding decades, many doctrines of ‘development’ and policies have influenced Ethiopian laws, and then side-lined in favour of newer versions that came up with a package of aspirations and prescriptions. However, the realization of the standards of living aspired by the vast majority of citizens still seems to be far away, while the rate of population growth and its corresponding pressure on the environment are steadily growing. The solution towards addressing these challenges thus seems to lie in the courage of citizens and policy makers to admit and address the triadic (and interwoven) economic, demographic and environmental challenges as they are visible facts that speak louder than the statistical figures of ‘economic growth.’ This calls for the need to demystify the generic unqualified reverence to the word ‘investment’ and rather examine the contribution of specific investments (or investment promotion packages in specific sectors) to the enhancement of domestic production capacity, sustainable economic development and rising standards of living at the grassroots.

References

[1] Investment Proclamation No. 769/2012.

[2] Susan Baker (2006), Sustainable Development. (London: Routledge), p. 5.

[3] Susan Baker et al, Editors (1997), The Politics of Sustainable Development: Theory, policy and practice within the European Union (New York & London: Routledge), page 12.

[6] K. R. Nayar (1994), Politics of 'Sustainable Development', Economic and Political Weekly , Vol. 29, No. 22, May 28,1994, p. 1328.

[8] Christina Voigt (2009), Sustainable Development as a Principle of International Law: Resolving Conflicts between Climate Measures and WTO Law (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers), pp. 374, 375.

[9] The Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 1995 (Hereinafter refereed to as the Ethiopian Constitution or the Constitution). Art. Art. 90(1).

[13] Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Growth and Transformation Plan 2010/11- 2014/15, Volume 1, Main Text, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (November 2010, Addis Ababa).

[14] Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Growth and Transformation Plan 2010/11- 2014/15, Volume 2, Policy Matrix, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (November 2010, Addis Ababa).

[15] The Tables are the following: Table 1: Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction; Table 2: Agriculture and Rural Development; Table 3: Trade and Industry Development; Tables 4, 5, 6: Mining Development; Road Development; Power and Energy; Table 7: Portable Water Supply and Irrigation Development; Table 8: Transportation and Communication; Table 9: Urban Development and Communication; Table 10: Education and Training; Table 11: Health and HIV/AIDS Prevention; Table 12: Capacity Building and Good Governance; Table 13: Children and Gender Development; Table 14: Culture and Tourism Development; Table 15: Environmental Protection; Table 16: Social Protection and Labour Market.

[16] Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy, <http://www.uncsd2012.org/content/documents/287CRGE%20Ethiopia%20Green%20Economy_Brochure.pdf> (Accessed 13 May 2013).

[17] <http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/production-capacity.html> (Accessed 20 April, 2013)

[18] Andrei Sulzenko and James Kalwarowksy. (2000). “A Policy Challenge for a Higher Standard of Living.” ISUMA: Canadian Journal of Policy Research. Volume 1, No. 1, Spring.

[20] Paul W. Kuznets (1988), “An East Asian Model of Economic Development: Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 36, No. 3, Supplement: Why Does Overcrowded, Resource-Poor East Asia Succeed: Lessons for the LDCs? (Apr., 1988), p. S21.

[21] World Economic Forum (2012), The World Competitiveness Report 2011-2012, Geneva, p. 4.

[27] Gallman, Robert E. (2003), Dictionary of American History, <http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3401804013.html> (Accessed: 10 Feb. 2012).

[28] Arthur C. Pigou (1932) The Economics of Welfare, Fourth Edition (London: McMillan & Co.). Part IV, Chapter XII.

[30] Amartya Sen (1985), The Standard of Living, Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Delivered at Cambridge University (March 11 -12, 1985).

[33] It is the notion that alcohol (as tranquilizer) can reduce the stimulant effects of khat (chat) so that the user can have sound sleep.

[34] Sen’s Footnote 27 in The Tanner Lectures on Human Values: See Resources, Values and Development (Oxford: Blackwell, and Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984), Introduction and Essays 13-20.

[35] Sen elaborates functionings and capabilities as follows:

A functioning is an achievement, whereas a capability is the ability to achieve. Functionings are, in a sense, more directly related to living conditions, since they are different aspects of living conditions. Capabilities, in contrast, are notions of freedom, in the positive sense: what real opportunities you have regarding the life you may lead. [FN 33].

(Tanner Lectures, pages 48-49).

[36] In Footnote 15 of the Tanner Lectures, Sen cites John Dewey Lectures, Journal of Philosophy 82 (1985).

[37] Sen’s Footnote 16 reads: “I am grateful to Bernard Williams for suggesting this way of clarifying the distinction between well-being and living standard (though he would have, I understand, drawn the boundaries somewhat differently).

[38] Sen, Tanner Lectures, supra note 30.

[41] Erik Thorbecke (2007), “The Evolution of the Development Doctrine, 1950 – 2005”, in Advancing Development: Core Themes in Global Commons, Mavrotas & Shorrocks, Editors (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), p. 13.

A number of empirical studies generated hypotheses that “highlighted the complex nature of the causal relationship between population growth and economic development” and explained migration to urban centers “as a function of urban--rural wage differentials weighted by the probability of finding urban employment.” (Thorbecke, p. 13).

[42] Yujiro Hayami and Yoshihisa Godo (2005), Development Economics: From the Poverty to the Wealth of Nations, 3rd Ed. (New York: Oxford University Press), p. 63.

[44] Debraj Ray (1998), Development Economics (New Jersey: Princeton University Press), p. 326.

[46] Hayami and Godo, supra note 42, p. 227.

[52] J. E. Meade (1967), “Population Explosion, the Standard of Living and Social Conflict”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 77, No. 306 (Jun., 1967), p. 236.

[55] W.T.S. Gould (2009), Population and Development (London & NY: Routledge), p. 63

[57] World Bank, World Development Report 2005, A Better Investment Climate for Everyone (New York: World Bank and Oxford University Press) p. 81

[58] Philip LeBel (1999), Measuring Sustainable Economic Development in Africa, ERAF, Center for Economic Research on Africa, Montclair State University, School of Business, May 1999, p. 14.

[61] Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MOFED) and the United Nations Country Team (2004), Millennium Development Goals Report: Challenges and Prospects for Ethiopia, March 2004, p. vii.

[64] United Nations, The Millennium Development Goals Report 2012 (New York, 2012), p. 66.

[65] Source: Official List, <http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Resources/Attach/Indicators/OfficialList2008.pdf> (Accessed 4 May 2013).

[66] <http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/rio20.html> (Accessed: 12 May 2013).

[67] <http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?menu=1300> (Accessed: 12 May 2013).

[68] Robert Kennedy’s Speech at University of Kansas, March 18, 1968. Posted at The Guardian 24 May 2012 <http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2012/may/24/robert-kennedy-gdp> (Accessed 6 May 2013).

[69] Author’s thematic translation.

[70] Edward R. Carr (2011), Delivering Development: Globalization’s Shoreline and the Road to a Sustainable Future (Palgrave Macmillan), p. 190.

[72] Bisrat Teshome, April 10, 2013, Addis Standard <http://addisstandard.com/ethiopias-hdiimproving-yet-among-the-worst-performers/> (Accessed 4 May, 2013).

[73] World Bank, Ethiopia at a Glance < Ethiopia at a Glance <http://devdata.worldbank.org/AAG/eth_aag.pdf> (Accessed 5 May 2013).

[75] [Total number of people enrolled in school divided by total number of school-age individuals. NB- Gross enrolment becomes greater than 100% due to grade repetition and entry at ages younger or older than the typical age at that grade level]

[76] World Bank, Ethiopia at a Glance , supra note 73.

[77] The figures are taken from World Bank, Ethiopia at a Glance, Ibid.

[78] World Economic Forum (2012), The World Competitiveness Report 2011-2012, supra note 21.

Bibliography

Major Laws and Policies

The Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 1995.

Investment Proclamation No. 769/2012.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Growth and Transformation Plan 2010/11- 2014/15, Volume 1, Main Text, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (November 2010, Addis Ababa).

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Growth and Transformation Plan 2010/11- 2014/15, Volume 2, Policy Matrix, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (November 2010, Addis Ababa).

Books and Articles

Baker, Susan (2006), Sustainable Development. (London: Routledge).

Baker, Susan et al, Editors (1997), The Politics of Sustainable Development: Theory, policy and practice within the European Union (New York & London: Routledge).

Carr, Edward R. (2011), Delivering Development: Globalization’s Shoreline and the Road to a Sustainable Future (Palgrave Macmillan).

Gould, W.T.S. (2009), Population and Development (London & NY: Routledge).

Hayami, Yujiro and Godo, Yoshihisa (2005), Development Economics: From the Poverty to the Wealth of Nations, 3rd Ed. (New York: Oxford University Press).

Kuznets, Paul W. (1988), “An East Asian Model of Economic Development: Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 36, No. 3, Supplement: Why Does Overcrowded, Resource-Poor East Asia Succeed: Lessons for the LDCs? (Apr., 1988).

LeBel Philip (1999), Measuring Sustainable Economic Development in Africa, ERAF, Center for Economic Research on Africa, Montclair State University, School of Business, May 1999.

Meade, J. E. (1967), “Population Explosion, the Standard of Living and Social Conflict”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 77, No. 306 (June 1967).

Nayar, K. R. (1994), Politics of 'Sustainable Development', Economic and Political Weekly , Vol. 29, No. 22, May 28,1994.

Pigou, Arthur C. (1932) The Economics of Welfare, Fourth Edition (London: McMillan & Co.). Part IV, Chapter XII.

Ray, Debraj (1998), Development Economics (New Jersey: Princeton University Press).

Sen, Amartya (1985), The Standard of Living, Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Delivered at Cambridge University (March 11 -12, 1985).

Sulzenko, Andrei and James Kalwarowksy. (2000). “A Policy Challenge for a Higher Standard of Living.” ISUMA: Canadian Journal of Policy Research. Volume 1, No. 1, Spring.

Thorbecke, Erik (2007), “The Evolution of the Development Doctrine, 1950 – 2005”, in Advancing Development: Core Themes in Global Commons, Mavrotas & Shorrocks, Editors (New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

Voigt, Christina (2009), Sustainable Development as a Principle of International Law: Resolving Conflicts between Climate Measures and WTO Law (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers).

Reports and others

<http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?menu=1300> (Accessed: 12 May 2013).

<http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/rio20.html> (Accessed: 12 May 2013).

<http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/production-capacity.html> (Accessed 20 April, 2013)

Bisrat Teshome, April 10, 2013, Addis Standard <http://addisstandard.com/ethiopias-hdiimproving-yet-among-the-worst-performers/> (Accessed 4 May, 2013).

Economic Research on Africa, Montclair State University, School of Business, May 1999.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy, <http://www.uncsd2012.org/content/documents/287CRGE%20Ethiopia%20Green%20Economy_Brochure.pdf> (Accessed 13 May 2013).

Gallman, Robert E. (2003), Dictionary of American History, <http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3401804013.html> (Accessed: 10 Feb. 2012).

Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MOFED) and the United Nations Country Team (2004), Millennium Development Goals Report: Challenges and Prospects for Ethiopia, March 2004.

Official List, <http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Resources/Attach/Indicators/OfficialList2008.pdf> (Accessed 4 May 2013).

Robert Kennedy’s Speech at University of Kansas, March 18, 1968. Posted at The Guardian 24 May 2012 <http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2012/may/24/robert-kennedy-gdp> (Accessed 6 May 2013).

United Nations, The Millennium Development Goals Report 2012 (New York, 2012).

World Bank, Ethiopia at a Glance < Ethiopia at a Glance. <http://devdata.worldbank.org/AAG/eth_aag.pdf> (Accessed 5 May 2013).

World Bank, World Development Report 2005, A Better Investment Climate for Everyone (New York: World Band and Oxford University Press).

World Economic Forum (2012), The World Competitiveness Report 2011-2012, Geneva.