Essay

David Walker, Civic Centres (2008).

Slough Town Hall | Hampstead Civic Centre: Master Plan | Hampstead Central Library | Hampstead Swimming Baths | Sunderland Civic Centre | Kensington & Chelsea Town Hall

Slough’s development from a Buckinghamshire market town to a thriving business centre benefiting from proximity to London and excellent travel links began in the 1920s and ’30s and continued after World War II. During the run-up to the Local Government Act (1958) and again during the review of councils in the mid 1960s, it attempted to secure independence from the county as an autonomous borough. On each occasion it approached Basil Spence to enlarge the neo-Georgian town hall which C.H. James & Bywaters had built with Roland Pierce in 1934-36. David Rock developed the original scheme in plans, elevations and perspectives produced between February and May of 1957 (and revised in November), while the second is represented only by sketches, many of them signed by Anthony Blee and dating from 1966-67. [1]

Rock’s proposals would have constituted a new building standing adjacent to the old on the junction site where Bath Road met with Ledger’s Road. Three storeys of office accommodation were laid out around a courtyard plan 160 feet broad by 170 feet deep, the internal court being exactly 80 feet square. From the north-east corner of this block there extended a low single-storey annexe, 90 feet by 90 feet across its main flanks.

Although conspicuously modern in appearance, the building’s simple rectilinear form and the classical regularity of its elevations provided a sympathetic complement to its predecessor. It was a three-storey concrete-framed structure with the ground floor of the principal Bath Road elevation to the north open-sided so as to permit access to the interior. On the upper floors the elevation was treated consistently across its length, the spandrels being marble and the continuous bands of metal-framed windows each 5 feet wide expressing the basic module which underpinned the scheme.

The east elevation towards Ledger’s Road was distinguished by a monolithic concrete canopy projecting at a slight angle over the doorway on that side, and supported by raking concrete struts. Floor-to-floor heights within the new building were lower than those of the old town hall, which was predominantly two-storey, and their wallheads coincided approximately 32 feet above the ground. The breadth and height of the north elevation’s bays were related on the Golden Section, from which the proportions of the original town hall had likewise been derived.

The three-storey block was set well back from the noise and bustle of Bath Road in line with the frontage of the old town hall. The projection of the single-storey annexe answered that of the earlier building’s east wing, so creating an informal forecourt. Access to the complex off the street was by means of a broad walkway extending through spacious lawns and past an open clock-tower of triangular plan which acted as a landmark. Within the forecourt the walkway was bordered by a pool on its eastern side.

Stepping into the entrance colonnade, the visitor was presented with simplified plans of the new building incised into a wall. Accommodation on each level was arranged round circuit corridors, with stairways in the angles of the court. This court was mostly laid to grass, with a single specimen tree. Its elevations contrasted markedly in their appearance, the double-height Rates Hall to the south being fully glazed between steel stanchions, while on the west the strong-rooms were concealed by a blind masonry frontage with water-jets gushing into a second pool. The offices on the eastern flank were expressed in the simple regular fashion that was characteristic of the exterior elevations, while the north front was different on every level, the top floor being open-sided to form a canteen gallery.

Slough’s inability to attain county borough status in 1958 resulted in the scheme being shelved, but the survival of Rock’s remarkable perspectives bears fitting testament to his draughtsmanship during his short career in Spence’s office. In 1966-67 when Slough made a second bid for municipal autonomy Anthony Blee produced new plans involving the substantial alteration and extension of the town hall but the proposals subsequently lapsed.

Hampstead Civic Centre: Master Plan

In 1956 Hampstead Borough Council purchased a site in the heart of Swiss Cottage on which to build a civic centre comprising administrative complex, library and swimming baths.[2]

The existing central library was bomb-damaged and acutely lacking in accommodation, while the central baths were obsolete, one pool being permanently out of use. A rumour that the centre was to be designed by Oswald Milne – seventy-four years old – who had formerly been the mayor, led to a flurry of letters in the newspapers which lasted several weeks.[3] The Council held a debate in November 1957 over whether a traditional or contemporary architectural style should be adopted, and in December local architects established the New Hampstead Society to press for an open competition and a progressive attitude towards the new buildings.[4] Four distinguished local residents – Dame Peggy Ashcroft, Sir Colin Anderson, Dr Julian Huxley, and John Summerson – together wrote to The Times to urge the adoption of a modern design for the complex.[5]

The Council considered that a competition would discourage eminent designers from submitting proposals since there would be little likelihood of success, and instead approached the R.I.B.A. (and possibly other institutions or individuals) to ask for the names of appropriately qualified practitioners. A list of candidates was prepared, some working in traditional and others in contemporary styles.[6] The final choice of Basil Spence, announced on 13 January 1958, met with cross-party support and general acceptance in the community. It was hailed as “a complete victory for the progressives.[7]

The first published proposals of January 1959 suggested that the civic suite, council chamber and council offices should extend across the relatively short frontage to Eton Avenue, and the swimming baths and gymnasium across

The total cost was estimated at £2 million, but in late June Henry Brooke, the Minister of Housing & Local Government and Hampstead’s own M.P., gave notice that he would not be willing to grant a loan sanction for the administrative buildings until the Royal Commission on London Government had issued its report.[9] Nevertheless, two revised layout plans appeared in Summer and Autumn 1959, perhaps as a result of traffic-flow decisions made by the L.C.C. at about that time.[10]

Brooke did give authority to proceed with sketch schemes for the library and the swimming baths, and these were approved by the Council in November 1960,[11] after which working drawings were prepared and the contract put out to tender. Although the necessary loan sanction was received in February 1961, [12] a Government economic squeeze in August led to delay[13] and Sir Robert McAlpine was unable to start construction until 31 December 1962[14] Sir Keith Joseph, who had succeeded Brooke as local government minister, laid the foundation stones on 31 July 1963[15] and the completed buildings were opened by Elizabeth II on 10 November that year [16]

The combined cost of library and baths, inclusive of professional fees, was £1,626,000. That was higher than the original estimates, but the buildings were generally thought to be successful. They appeared in the local and national press, were widely reproduced in architectural and other periodicals, and numerous aspects proved of interest to specialist publications. The buildings were even used as the backdrop for a fashion shoot in Queen. [17]

Any hope of an administrative complex was finally abandoned when it became clear that, under the provisions of the London Government Act (1963), Hampstead would be merged with St Pancras to form the new Borough of Camden. Thereafter a strong current of opinion held that the remaining site should be developed as a cultural centre, including a concert hall and assembly hall. [18] Some people, however, expressed concern that the centre should not be exclusively “highbrow” but should cater for everyone in Camden, providing affordable housing, welfare facilities and open spaces in which people could relax.

It was quickly realised that these ideas were not incompatible. The Council actively encouraged local residents and organisations to put forward their proposals [19] Suggestions included art galleries and an arts-and-crafts workshop; an “experimental” theatre; music halls; sports facilities of all kinds; a scooter workshop; a zoo; high density housing; old people’s residences and a youth hostel; a crèche; restaurants, bars, cafés and pubs; specialised shops; a hotel; a welfare centre, clinic and counselling centre; additional council offices; a department store or shopping arcade; and small factories. There was even a suggestion that the site be used for an airport, but that was quickly squashed. [20] A discussion forum was organized under the chairmanship of Lord Cottesloe, formerly head of the Arts Council. [21]

The Town Clerk produced a report on the site early in 1966. [22] Four well-known management consultancies were asked how they would develop the many different suggestions for the site into a clear plan which would serve as the basis for a new brief to the architects. [23] The Council subsequently chose Associated Industrial Consultants to engage in a further detailed survey of local residents, acknowledged experts in the arts and leisure, and promoters and impresarios. A.I.C.’s report produced in 1967 ran to four volumes. [24] Noting that demand for leisure services was rising sharply, and that 620,000 people lived within a three-mile radius of the site, they explained that “The Centre should have an informal, relaxed atmosphere. It should be a place to go with friends and to meet friends, a place to sit and watch life go by and to take part in a great variety of activity. … The Centre should inform visitors of the opportunities it has to offer, but should not try to educate or improve its visitors.” The Council enlarged the site by acquiring additional ground towards College Road from the G.L.C. This not only allowed for more buildings, but also for greater flexibility in their planning. [25]

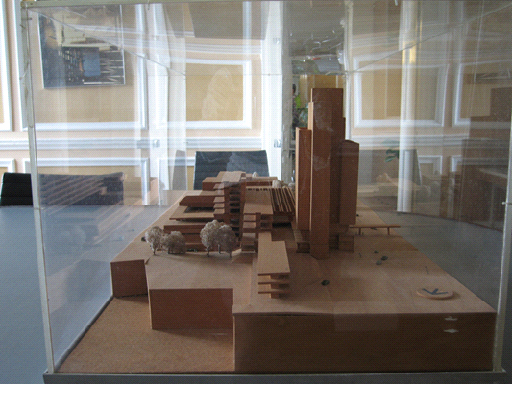

Drawings and models produced on 30 September 1969 [26] represented a single large complex which was quite deliberately inward-looking in nature, focused around a central covered piazza, on account of the busy streets on each side. A hotel with 200 bedrooms, shops and National Provincial Bank branch stood towards the north end of the site nearest the commercial centre in Finchley Road, while the sports hall was situated over the entrance to the tube station where it could act as a noise barrier for the arts centre and sculpture court. The site also provided a multipurpose hall for 1,000 people attending concerts or conferences; there was a theatre, and one or two small cinemas; a hostel for young people or for students, a welfare centre, and additional Council offices. Attractive walkways linked the complex together, and the roofs were paved or laid out as gardens for the pleasure of residents and visitors, and to create a verdant outlook for the surrounding high buildings. Part of the Centre was underground to keep the overall height down, and there was a subterranean car-park which could accommodate 750 cars. “Much care has been taken to minimise the scale of the buildings in relation to their surroundings,” The Financial Times commented on 1 October, “The large and comprehensive nature of the structure has been played down, the only section to be given independent expression being the hotel.”

“The site has more potential than the South Bank: people should be attracted here in the evening because there will be a lot going on,” Jack Bonnington told The Evening Standard on 30 September, while to The Highgate & Hampstead Express he explained on 3 October that “The whole site will work as one building, not as a series of individual blocks. We also hope that so many activities closely bound together in this way will mean that the Centre will be alive all the time.” On the same day The Camden & St Pancras Chronicle declared that “The scheme will provide the Borough of Camden with the finest arts and sports centre in the country, if not in Europe.” Part of the complex was allocated to the Central School for Speech & Drama which wanted to rebuild its existing premises on the site, and it was hoped that one of the Colleges of Music might also establish itself at the Centre.

All in all it seemed worth the estimated £10 million cost which would be spread by phasing construction in four stages. The first was to include the hotel, since it was intended that the promoters should fund other facilities to minimise the impact on local ratepayers. Once the Centre was established, the revenue from its commercial premises (the shops and bank were also included within the first phase) would help to keep it afloat, and it would attract grants from the Inner London Education Authority. As The Express & News declared on 17 November, the scheme promised “A swinging Swiss Cottage,” but it had already been overtaken by events.

Under the terms of the Development of Tourism Act, 1969, the promoters of hotels were entitled to Government grants and loans if they started and completed their buildings within the following few years. In such circumstances the Council felt a much larger hotel would be necessary to attract major developers, and they therefore authorised an increase to 500 bedrooms, and instructed the architects to revise their designs for the rest of the Centre so that it should not be overwhelmed.

These revised designs were completed by November 1971, passed by the Planning Committee on 3 December and approved by the Royal Fine Art Commission shortly afterwards. Construction began before Christmas but did not get far, stalled, no doubt, by economic factors. Jack Bonnington prepared further schemes for the site between 1973 and 1976. [27]

The Swiss Cottage Library was at once distinguished by the simplicity of its general appearance and the great sophistication of its concept, characteristics which were carried into every aspect of its design. [28] Oval on plan, its semicircular bows were 75 feet in diameter and its parallel flanks contributed to a total length of 255 feet. It comprised three storeys of equal height, rising over a basement which was mostly hidden beneath ground but partly revealed where the site sloped down gently towards Adelaide Road at the south-east end.

Both basement and ground floors were largely given over to library services including a book-stack, and the ground floor was accordingly faced in Portland stone to form a plinth, very solid except for the occasional door and window openings. The superstructure of the first and second floors did not rest on the plinth directly, but appeared to float above the low clerestorey which extended round much of the plinth’s wallhead. This superstructure comprising of the public accommodation was of a lighter, more open and elaborate appearance, being lined with vertical fins of pre-cast concrete to produce a consistent effect, even if the spaces inside varied widely in size and purpose, and the windows between them were consequently of different sizes. The fins helped diffuse sunlight and moderate solar gain within the building and thus contributed much to its internal ambience.

The floor and roof slabs of the structure were supported on columns, most of which were concealed within the envelope walls or partitions. At the north-west bow, however, a ring of bush-hammered columns was exposed at ground level to form a porch sheltering the recessed main entrance. The downward overhangs of the fins gave the impression that the porch was lower than was actually the case, so increasing the sense of intimacy.

A draught lobby opened into an entrance hall with book issue and return counters arranged on either side. In keeping with the simplicity of the exterior, the hall was very restrained in character. The floor was paved and the walls were panelled with white terrazzo, while the fluorescent ceiling lights were concealed by slats of white beech. Lifts for the use of the disabled and infirm were provided off a corridor, but most visitors proceeded up the main stair centred opposite the entrance to reach the exhibition foyer at first floor level. The stair was also faced in white terrazzo, against which its dark afromosia handrails provided striking accents.

The exhibition foyer extended through most of the building’s length between the curved ends. It was double-height but the upper storey landings, including the central “bridge” formed by the deputy librarian and secretary’s rooms, were glazed in so as to produce two top-lit wells.

This bridge served a practical purpose since it allowed for supervision of the lending and reference libraries, likewise double-height, which opened off the foyer within the end-bays. The bookcases within the central floor areas were arranged in a radial pattern to allow uninterrupted views (all the furnishings were designed by the architects) and additional shelving was provided within the curvature of the bows. The windows between these shelves reached almost down to floor level to allow views out and maximise natural light, which was again supplemented by roof cupolae.

In both the lending and the reference libraries a pair of twin spiral stairways rose from first floor, where the more popular titles were kept, to the second floor landings reserved for in-depth consultation of less frequented books. The reference library’s upper landing also accommodated forty student carrels, two of which were specially designed for drawing and typing. The stairs themselves were notably elegant in appearance, with simple steel balusters supporting afromosia kite-winders and handrails.

On the south-west side of the central foyer a children’s library, exhibition area and study enjoyed a bright outlook onto Avenue Road, while the periodicals, workroom, and bibliography and reservations room occupied the more sheltered north-east side. Similarly on second floor, a music library with gramophones and records was provided on the south-west side and a philosophy library on the north-east, together with two general offices and the librarian’s own room.

Standing next to the Library on Adelaide Road and complementing it in style, the Swimming Baths occupied a footprint that was almost square, but the varying height of its elevations reflected both the internal planning and structure. [29] The most important spaces – the major and minor pool halls, the teaching pool and gymnasium – rose well above the squash courts, changing rooms, café and circulation areas which linked them all together.

The major and minor pool halls on the south-east side of the block presented a consistent three-storey frontage to the street, similar in height to the Library. The teaching pool and gymnasium on the north-west frontage, facing the pedestrian concourse, were rather smaller spaces and therefore did not rise so high, but they nevertheless stood tall above the entrance foyer and the corridor separating them from the main pools.

The foyer was approached from the pedestrian concourse by means of a bridge over the basement, which was exposed on this side; the entrance doors themselves were sheltered by a canopy. The ramp leading into the basement allowed large parties and disabled visitors to enter the building directly at pool level. It also gave access to the service yard shared between the Baths and the Library.

For much of their height the Baths presented simple Portland stone elevations to match the Library plinth; the windows of the main pool hall were, however, concealed behind long horizontal brise-soleil fins or louvres. Externally these fins gave the building a vibrant modern appearance, and acted as a foil to the vertical fins of the Library. Internally, the manner in which they modulated the sunlight gave the Baths a very distinctive atmosphere. During the summer months they resulted in dramatic shadows being cast upon the walls; they were carefully dimensioned to permit clear views out, to reduce solar gain (and thus the need for air-conditioning) in hot weather, and yet still allow good lighting conditions in winter. Projecting from the centre of the street elevation between the pool halls was a sunbathing terrace, also used for physical training classes, the sides of which were decorated with sculpture by William Mitchell: its vigorous, blocky, tightly controlled modelling provided an important focal point. Above the fins, the building rose into a wallhead distinguished by its use of concrete panels faced in black basalt aggregate, a contrast to the light Portland.

The major and minor pools shared pre-bathing facilities at entrance level, concealed within their raked seating galleries, and had their own changing rooms and clothes stores downstairs at the pool-side. In winter, a floor could be laid over the minor pool to convert it for use as additional squash or badminton courts. The café for refreshments on first floor opened onto a terrace on the south-west flank, extending towards the Library.

Like the Library, the external restraint was mirrored in the interiors which were predominantly white with splashes of colour – black and green terrazzo within the main staircase from entrance hall to pool level, blue and tangerine doors to the changing rooms, and blue tile-work within the pools themselves.

Sunderland first proposed to build a new town hall as early as 1939, but the war intervened, the town suffered in the bombing, and its core was re-planned in the aftermath of the peace. It would be another twenty years before the Council, prompted by local authority reforms and a growing population, suggested that a civic centre should be built within Mowbray Park, the town’s attractive Victorian pleasure-ground. In a turn of events remarkably similar to those at Hampstead, this provoked the architect George Hawkins to found the Sunderland Civic Society in 1960, and Miss Dalrymple-Smith, its “moving spirit,” to organize a petition against the loss of a valued recreational amenity. A Public Inquiry found in favour of the objectors, and the Council thereafter decided to build its civic centre within West Park, adjacent to Mowbray Park across Burdon Road. [30] West Park was close to the town’s business and shopping district, although separated from it by a railway cutting.

The Council established a sub-committee to select an architect, [31] and on 14 October 1963 a meeting was sought with Basil Spence to establish whether he would take the commission. At the time it was optimistically envisaged that the cost would be about £1½ million, and that work would be completed in 1968. Spence addressed the Council on 18 December 1963 and his appointment was confirmed on 12 February the following year, just before he departed for New Zealand to advise on the parliament buildings there. [32] In his absence, Jack Bonnington discussed the programme and accommodation schedule with the clients, and it was agreed that two models should be produced to accompany the sketch proposals and final drawings. [33] Although Spence cleared his diary between April and September so he could concentrate on the project, in the event it was Bonnington who assumed responsibility for developing the scheme, perhaps because the Council was unable to establish its accommodation requirements until 14 July and other commitments were pressing. The final designs and model were presented to, and approved by, a special meeting of the Council on 25 October 1965. [34] They had to be revised, however, when the Ministry of Housing & Local Government took exception to the banqueting and reception halls in 1966, and insisted on their omission. [35]

The designs represented, as was acknowledged at the time, a thoughtful reinvention of traditional town halls, and one more in keeping with recent ideas of what local government ought to be. [36] Since the gentle rise of the site naturally dominated its surroundings, it was decided to lay the building out as a series of four essentially hexagonal blocks across the ridge from north to south. Of these blocks it was the central pair, devoted to the provision of public services, which were easily the most prominent. They were nearly the same size, rose taller than their neighbours either three or four storeys above the ground, and were regular in form so that each face was similar in length. On the eastern flank overlooking Mowbray Park they presented an almost symmetrical frontage, being linked together by a common entrance block that was itself a small hexagon on plan.

On the north side nearest the town centre, the car-park was arranged in line with the central blocks, but being at the foot of the slope rose comparatively low, and its bays were canted on the east flank only. It was an open-sided columnar structure of reinforced concrete – hinting at the structure of the main hexagons – and rose in tiers, each storey being recessed in relation to the one beneath so as to create a stepped appearance. It was large enough to accommodate over 500 vehicles.

The southernmost block which contained the Civic Suite and Council Chamber – the traditional focus of a town hall – was a true hexagon on plan, but set well back from the principal eastern frontage. It overlooked a townscape of Victorian houses and churches, and an approach avenue which was lined with elm trees. It was predominantly two-storey in height, but the Council Chamber’s tall, continuously glazed elevation could be seen rising up inside, contrasting with the general solidity of the structure as a whole.

The design gained great strength from the manner in which it was built up across its length from low blocks at each end to taller blocks in the centre. The hexagons’ brick-faced, blind and battered plinths endowed it with the stability of a fortress – indeed, the principal frontage rose from above a rocky outcrop. Again like a fortress, the hexagons were formed around spacious courts. Alternating with the tough-looking wall-planes – reinforced concrete faced in brick tile – continuous window-bands extended across the frontages at each level, and watched over the town on every side.

To the north of the complex, the approach slope was ingeniously paved over as a ramped terrace that incorporated angled flights of steps within its rise. The triangular form of its paving slabs anticipated the hexagonal plan-forms of the Centre itself. Simple lamp-standards of contemporary pattern contributed vertical accents, and polished metal handrails added elements of sparkle to the bold geometry of the scheme. The overall result was not only striking in visual terms, but also practical since the slope provided natural drainage, and allowed access for disabled and infirm visitors. It attracted considerable interest and admiration from the architectural press.

Another means of approach was provided by the bridge which spanned from Mowbray Park across the ravine of Burdon Road to arrive in front of the main entrance, which was formed within the link between the two central hexagons. The entrance front was fully glazed at ground floor level, with polished metal door- and window-frames again providing highlights.

The reception hall took the form of an open well rising through the height of three storeys. Its choice of materials – paved floors, concrete columns and brickwork galleries fitted with metal handrails – reiterated the finishes of the exterior. Each of the Council’s eighteen departments occupied either half or a whole floor of one of the central hexagons, and each had its own public entrance opening off the well, so that visitors could find them easily. Like all the stairs throughout the building, the main stair next to the reception desk was of relatively modest dimensions and set into a recess. This was a very obvious break with the grand staircases in classic town halls of old, but practical in terms of space and cost.

The hexagon blocks not only resulted in efficient planning, good day-lighting and interesting visual effects, but also permitted extension if required: should the public services within the central hexagons require more space, it would be relatively straightforward to construct an additional hexagon between them immediately to the west, without disturbing the appearance of the Mowbray Park frontage.

The hexagons were planned on a grid of equilateral triangles. The main grid comprised of triangles which were 20 feet long across each side, columns rising up from the intersections to support the floor-slabs. Within the larger grid was a subsidiary grid of smaller triangles, the sides of which were just 5 feet long; this smaller module was expressed externally in the dimensions of the window-frames, which were each 5 feet square. Walking through the building from one courtyard to the next, the triangular grid structure could be seen clearly within the soffits of the floor-slabs above.

The internal partitions were of plastered blockwork. They could be adjusted along the lines of the minor grid to allow for expansion and contraction of departments over time. Because of the grid they were arranged at angles of 120 (rather than 90) degrees to each other, but as Lance Wright observed this created a pleasant sense of spaciousness. Generally, the floors were carpeted with nylon felt, and ceilings lined with acoustic lath or timber-boarding, to reduce the background noise to a minimum. The supply of services was neatly incorporated within the structure of the building, having been undertaken by the architects’ in-house engineering department.

Within the southern hexagonal block the large courtyard provided an open-air venue for ceremonial occasions; the councillors’ subterranean garage, with space for 130 cars, was concealed beneath it. The Council Chamber was itself a hexagon on plan, based on a modified version of the triangular grid. Its internal walls were of fair-faced brick with open joints, and the slatted timber ceiling rose in a shallow rake towards a central oculus. The Civic Suite’s entrance hall was distinguished by a remarkable chandelier. It was composed of an extended lattice of hexagons formed from polished metal tubes, the bulbs at the nodal points creating an attractive lighting pattern.

The construction contract was awarded to John Laing, who offered to build for £3,209,500. The high cost of such an ambitious local government project within a town that suffered from widespread deprivation was inevitably criticized, but a desire to provide work for local people was an important consideration for the Council in commissioning the scheme. Laing took possession of the site on 29 January 1968 and the foundation panel was laid by Sunderland’s mayor, Alderman Wikinson, on 24 September. The completed building was opened by Princess Margaret on 5 November 1970.

Kensington & Chelsea Town Hall

Like Sunderland, the Royal Borough of Kensington initially proposed to build a new town hall before the Second World War. [37] In February 1946 it purchased the Abbey Site, [38] three-and-a-half acres to the north of the High Street, from Lord Ilchester’s estate at a bargain price (even then) of £86,000. Its intentions of constructing a civic centre comprising both town hall and library were at first held back by building restrictions in force during the post-war period, then nearly foiled when the Soviet Union asked that the site be turned over for an embassy surrounded by a perimeter wall sixty feet high. This request was withdrawn in the face of vociferous opposition from the Council and local residents. [39]

Thereafter the Library was built at the south end of the site between 1957 and 1960 to a classical design by Vincent Harris. Although Kensington intended to build its new town hall in a complementary style, the Ministry of Housing & Local Government refused to sanction further progress until the Royal Commission on London Government had completed its review.

This review led to the London Government Act, under the provisions of which Kensington was to merge with Chelsea. The new Council, elected in 1964, not only assumed the responsibilities of its constituent boroughs but also many responsibilities – and several hundred staff – of the L.C.C. A single town hall which could accommodate all the Council’s departments now became a still greater priority than it had been before. However, the Council seems to have been stung when “Anti-Ugly” activists identified the Library as a target for condemnation. Recognizing that Harris, born 1876, must be nearing retirement, and that the town hall’s development would be a protracted affair, it concluded that it must turn to a younger practitioner for a more modern design. In November 1964 the Civic Buildings Committee sought advice from Basil Spence in respect of possible candidates. [40]

It was tactfully suggested that Spence might submit his own proposals, if his busy personal schedule allowed. There was also some thought of redeveloping the area east of the Abbey Site towards St Mary Abbott’s Church as shops and offices. [41] Spence indicated that he would be interested in the commission, [42] the Committee recommended on 16 December that he be appointed architect, and this was ratified by the full Council on 7 January 1965.

Spence briefly considered an office tower with the council chamber, civic suite and public halls accommodated in lower buildings around its base, or a heavy block perhaps of pyramidal form, but soon concluded that either of these would be detrimental to the site’s amenity and its residential surroundings. He therefore determined on a courtyard building which in height and materials would relate both to the Library and neighbouring houses, and would preserve the sense of openness and most of the existing trees. [43]

His ideas first saw light of day on 9 February 1965, when he sketched them out on a menu-card while travelling with Council delegates on the “Brighton Belle” Pullman service to visit the University of Sussex. [44] In early June the Council sent him an accommodation schedule and within a week he had developed his proposals into “an outline solution,” of which a rough model was made. [45] This scheme was priced by Reynolds & Young at approximately £2½ million in August, [46] and when Spence presented it to the Civic Buildings Committee on 6 September it received a very favourable reception. However, news that the redevelopment to the east of the Abbey Site might not proceed at once resulted in revised sketch designs, a perspective and model [47] which the relevant committees accepted in mid November, and the Royal Fine Art Commission on 8 December. [48] The Council made provision for expenditure of £2,815,000 in its capital estimates between 1965 and 1969. [49]

Spence was then instructed to prepare working drawings while the Council sought an Office Development Permit from the Board of Trade. In May 1966 the Local Government Minister said there could be no prospect of a loan sanction in the near future and work virtually halted. However, the Permit was granted in February 1967, the G.L.C. gave its consent in March, and in June the Minister advised the Council that a Public Inquiry should be held because of the project’s importance and the large number of objectors. This took place on 12 December, the Minister approved the proposals in November 1968, and early in 1969 he agreed the loan sanction, subject to prevailing economic conditions. [50]

By then the Council had reassessed the accommodation schedule in the light of new legislation which further increased its responsibilities, and found that these could not be met within the scheme as currently proposed. Councillor Charles Muller recalled visiting Spence at Canonbury Place to tell him that the town hall must be redesigned again:

“Some architects might have given up or tried to persuade one that no alternative was possible. Basil sat for two minutes in silence, went to his drawing board and in half an hour had produced new sketches which fully met our requirements.” [51]

The new scheme, which was approved in May 1970, was similar in concept and overall mass to its predecessors, but actually rose one storey less above ground. A model was made, working drawings were completed in 1971, and the contract put out to tender in July. When the offers were opened in September, the best was that submitted by Taylor Woodrow, which was also involved in development proposals on the south side of the High Street. Their offer price of £6½ million, more than double the estimate for the original scheme of 1965, inevitably generated controversy at a time of national financial difficulties. [52] The site was cleared and excavation work began in January 1972. Gordon Collins was appointed project architect, the working drawings being prepared at Fitzroy Square.

As built, the Town Hall comprised of eight storeys, five above street-level, a basement partially exposed where the site fell away towards the south, and two sub-basements. [53] The core of the building was its office accommodation, a large courtyard block which was essentially square in the interests of efficiency, although the varied treatment of the flank elevations to Hornton Street and Campden Hill Road implied a more picturesque approach to composition and diminished any sense of a substantial mass that would have excessively dominated its surroundings. The Borough’s anticipated requirements were so extensive that maximum use had to be made of the oblong site, and so additional office wings were built out on the north side in line with Holland Street, while to the south two blocks containing the Great Hall and the Council Chamber overlooked a ceremonial forecourt and together framed the building’s principal entrance.

In height and materials the Town Hall was designed to relate both to the Central Library on the opposite side of the forecourt, and to the houses surrounding it on the three other sides. Although the structure was generally of reinforced concrete cast in situ, it was clad with warm red bricks – Redland Holbrook – which corresponded quite closely to the Library in colour and suggested a feeling of domesticity appropriate to the residential surroundings. They also corresponded to the Library’s Roman brickwork in another respect, their unusually long and slim proportions. They were in fact metric and modular, 30 centimetres long, 10 centimetres in height and 7½ centimetres deep. In keeping with national policy at the time, the final working drawings were prepared using metric rather than imperial modules, and Spence was convinced that these bricks represented an imminent revolution in the construction industry. That was not actually the case, and the Town Hall was the only building in the country to use them. The brickwork was, however, of exceptional quality, and given an extra jagged vivacity by the pointing, which was of a much lighter colour.

The forms of the Council Chamber, on the visitor’s left when approaching the main entrance, and the Great Hall towards the right, were very powerfully modelled. On plan, the Chamber and the Hall were of similar dimensions, square with canted corners, but they were nevertheless quite different in appearance.

The Hall projected further forward, its battered plinth concealing the basement on this side. Blind walls rose almost the full height of the main block to be crowned with a concrete coping. The Hall relied on its substantial size and its simple form without any fenestration for effect. The Chamber, however, as the very seat of local government within the Borough, was raised up to first floor level, being supported in mid-air above an octagonal pool of water. Within this pool – the sides of which were battered to answer the Great Hall’s plinth – four cruciform columns of white bush-hammered concrete supported brackets of the same material, and these in turn cradled the Chamber’s intricately geometrical floor-plate. The concrete structure was clearly emphasized by its colour-contrast with the red brick walls which were again almost windowless, and which rose into a heavy entablature of ribbed concrete and a truncated pyramid roof. The water – within which the reflection of the floor-plate could be seen clearly – flowed at a gentle and even rate from each side of the pool towards a central aperture before gushing down and then being re-circulated. For additional drama, the cruciform columns were illuminated at night by underwater floodlights. [54]

Between the Great Hall and the Council Chamber, two short flights of steps led up to the ground floor level and the building interior, passing beneath a row of first floor mullioned oriels. These oriels were double-height – equivalent to two storeys of office accommodation – and took advantage of the fall in the ground to provide the Council Suite with an appropriate sense of dignity. The western oriel nearest the Great Hall accessed an open gallery from which the mayor could address assemblies gathered in the forecourt below.

The repeated use of oriels and canted corners, as opposed to right-angled forms, endowed the whole composition with additional vitality and allowed for more interesting views of the surroundings. Further to these ends, the ground floor of the office block was partly open-sided, with the upper storeys supported on colonnades. In his earlier proposals, Spence had intended that the central courtyard would be much larger, and would preserve most of the existing trees. He wanted it to seem welcoming to those visiting the offices arranged on each side – the antithesis of the grand foyer in a traditional town hall – and, equally, to passers-by seeking an attractive open space in which to relax, or simply walk through. He hoped by such means to integrate local government both physically and psychologically in the heart of its community, an important consideration given the Town Hall’s substantial cost.

Something of this concept was diminished in the final scheme produced after the Council’s requirements had become fully apparent. The courtyard was reduced in size, and the surrounding colonnade became much deeper and darker in consequence, but this change in character was cleverly exploited. The colonnade, and the reception foyer and vestibule which were partly enclosed with amber-tinted glass, were lit by simple ceiling lights to produce an attractive pattern of illumination piercing through the gloom. The concrete soffits were grit-blasted to give them a more interesting appearance and texture.

The courtyard was still large enough for outdoor receptions. Square on plan, its pavement was laid in brick to match the elevations enclosing it on all four sides. Entrances were provided for road vehicles in the Hornton Street and Campden Hill Road flanks. The courtyard contained a bronze sculpture by Barbara Hepworth, River Form, [55] and two trees, one of which, a giant redwood, was planted in memory of Sir Winston Churchill. This latter was surrounded by a circular bench, the back-rest of which was lettered with the words “a giant amongst trees in honour of a giant amongst men.” [56]

The external elevations of the Town Hall were characterised by their envelope walls of red brick, alternating with continuous bands of square tinted windows set between bronzed aluminium mullions. [57] The Hornton Street elevation was quite simple, partly to avoid competing with the neighbouring houses, but also because of uncertainty over future development on their site. North of the colonnade, the elevation at first floor was canted over the pavement to answer the oriels of the Council Suite, but the second and third floors were progressively stepped back to give added interest to the design and reduce the overall sense of mass.

On the north flank towards Holland Street, two office wings projected boldly forward to frame the approach to the Entrance Hall, Information Centre and Rates Hall. In style, the elevations of these wings corresponded with the central block exactly, red brick walls alternating with bands of tinted windows, but they were angled out in line with the road to make maximum use of this end of the site, and to contribute to the bold modelling which was characteristic of the scheme.

Of these two wings, the larger to the west – known as Niddry House [58] - was returned into Campden Hill Road, unusually at a right-angle rather than a canted corner. But once again the sense of a solid block was reduced, and a diagonal element at least suggested, by the manner in which its three storeys were cantilevered out one above the other to produce a dramatically stepped profile. The Campden Hill Road frontage divided into three long bays connected by shorter links: the north bay continued the cantilever treatment, while those in the middle and to the south adopted a similar appearance to the Hornton Street elevation. The great length of the Campden Hill Road frontage was substantially screened by a line of trees extending from end to end.

Although in executed form the Town Hall was a storey lower than Spence had originally intended, by adopting an open-plan layout the offices could still accommodate the Council’s 1,250 staff. [59] The building’s total mass was similar to that suggested in the earlier proposals since the height of the storeys was increased to provide for air-conditioning equipment above the suspended ceilings, and so guarantee a comfortable environment. The floors were carpeted, and the tinted glass moderated the heat and glare of the sun. Particular care was taken to ensure that the basement rooms were pleasant for their occupants.

The attic was recessed so far back on each side as to be invisible from street-level. It accommodated most of the mechanical plant and two flats (each with three bedrooms) on the northern front. One of these flats was occupied by the building superintendent, who doubled as mace-bearer, and the other by the resident engineer. The basements provided not only office space, but an archival store, services, and parking for 400 cars, accessible by means of ramps on either side of the Library. [60] The battered form of the basements’ brick ventilator shafts picked up on the theme of the Great Hall’s plinth and the Council Chamber’s pool.

The main stair opening off the reception foyer was quite tightly planned, but nevertheless of distinguished character with broad flights which bore up the weight of the half-landings without any support from the surrounding walls. The stair was guarded on each side by stainless steel balusters framing panes of smoked glass. The most impressive interiors were, naturally, those of the Civic Suite – in particular the Council Chamber – and the two Halls. In a nod to tradition the Chamber walls were lined with ribbed sweet chestnut and its ceiling veneered in the same material, but behind the desk occupied by the mayor and his deputy was a sculpture in Portland stone representing the Borough’s coat-of-arms. The Chamber accommodated seventy councillors whose raked seating (upholstered in leather) was arranged round the mayor’s desk in a hemicycle; there was also provision for thirteen Council officials, nine news reporters and a number of guests, while sixty members of the public could view proceedings from a gallery which had its own separate entrance from street-level. The Chamber featured state-of-the-art sound amplification and a vote-counting system (“the like of which cannot be found anywhere in Europe” [61] ) that flashed up results on a digital display. The main source of light was an abstract composition of transparent cuboid forms which was suspended within the profiled ceiling.

The Great and Small Halls were both approached through a common vestibule occupying the south-west corner of the courtyard block. They could either be used separately, or jointly for larger gatherings. The Great Hall accommodated 753 people at ground level, 95 in the gallery, and two groups of six in the boxes. It had a maple strip floor suitable for dancing, walls of Redland Southwater brick, and a fibrous plaster ceiling which was formed between the roof’s steel members to produce a honeycomb effect. The stage incorporated a lift capable of raising chairs or a piano from the basement dressing area. Behind the stage, the expanse of wall was relieved by three gigantic crowns and a bishop’s mitre, again deriving from the Borough crest, their forms picked out in raised brickwork. [62]

The Small Hall at first floor level accommodated 190 people. It also had a stage and a floor of maple strip, walls lined with cedar of Lebanon, and a ceiling which comprised of timber beams suspended from the concrete slab above. Both Halls – and the Council Suite – were conveniently close to the buffet and bar facilities, and both could be used for cinema performances and slideshows.

The construction of the Town Hall was scheduled for completion in 1975, but a familiar combination of difficult ground conditions, inclement weather and industrial action resulted in the deadline being missed. At a time when labour costs were rising sharply, this put a severe financial strain on both Taylor Woodrow and its sub-contractors, several of whom threatened to walk out from the site. [63] It was only by agreeing an additional payment of £800,000 that the Council managed to secure the building’s substantial completion by a revised deadline of 29 November 1976.

The account for the Town Hall was £11.6 million; when fittings, site-costs and fees were included, that rose to £13.4 million. [64] The cost of the car-park alone was almost exactly equal to the original estimates for the whole building in 1965 and, during a period of severe local authority cutbacks, such expenditure provoked a storm of protest. [65] However, the brief had been revised so often, and the value of money so eroded by inflation, that it was hard to say whether the Council had paid over the odds for a town hall finished to an extravagant standard, or had in fact secured an exceptional bargain. Perhaps it all depended on one’s attitude to life, and which measure of inflation one chose to use. Council Leader Sir Malby Crofton was surely correct to observe that, provided the value of money continued to fall – which it did – the true burden on the ratepayer would diminish all the time. The Town Hall was officially opened by Princess Anne on 31 May 1977, coinciding with the Silver Jubilee celebrations. So many years later, the quality of the building remains self-evident, and its cost can be forgotten.

[2] This background section has been derived from Council minutes and files at the Local Studies Library, Holborn.

[3] Hampstead & Highgate Express, 22 November 1957, p. 1.

[4] Hampstead & Highgate Express, 20 December 1957, p. 1.

[5] Times, 17 December 1957, p. 9.

[6] Council minutes, Planning Committee reports, 8 February 1957, 8 November 1957, and 10 January 1958.

[7] Hampstead & Highgate Express, 13 January 1958, p. 1, and 17 January 1958, p. 1.

[8]Hampstead & Highgate Express, Hampstead News and Kilburn Times, 23 January 1959; Times, 23 January and 21 February 1959. See also reports in the architectural periodicals.

[9] Hampstead & Highgate Express, 26 June 1959, p. 1.

[10] Hampstead & Highgate Express, 7 October 1960, p. 3.

[11] Times, 22 November 1960, pp. 12, 16.

[12] Hampstead & Highgate Express, Hampstead News and Kilburn Times, 24 February 1961.

[13] Hampstead & Highgate Express and Hampstead News, 18 August 1961.

[14] Hampstead & Highgate Express and Hampstead News, 4 January 1963. For details of tenders, see Council minutes for 6 September 1962.

[15] Hampstead & Highgate Express, 2 August 1963, p. 1.

[16] Illustrated London News, 5 September 1964; Times, 10 and 11 November 1964; Guardian, 10 November 1964; Hampstead & Highgate Express, Hampstead News and Kilburn Times, 13 November 1964.

[17] Queen, 16 June 1965, “The Right Angles.”

[18] These were mooted in November 1963, but the Council minutes are missing.

[19] Kilburn Times, 30 December 1966.

[20] Hampstead News, 3 February 1967, Evening Standard, 10 February 1967, Hampstead & Highgate Express, 24 February 1967.

[21] Express & News, 16 February 1967.

[22] Council minutes, Planning & Development Committee reports, 31 January 1966.

[23] Council minutes, 21 December 1966.

[24] Council minutes, report of Special Redevelopment Committee, 12 January 1967; A.I.C. submission in Local Studies Library. Its contents were reported in the press, e.g., The Hampstead & Highgate Express and The Guardian on 17 November.

[25] Council minutes, 20 July 1966.

[26] Express & News and Evening Standard, 30 November 1969; Times, Financial Times and Guardian, 1 October 1969; Hampstead & Highgate Express, Hampstead News and Camden & St Pancras Chronicle, 3 October 1969.

[27] A few drawings relating to these schemes are kept in the Local Studies Library.

[28] This description of the Library has been based on reports in the architectural periodicals and the author’s personal inspection.

[29] This building has been demolished, and the description has therefore been based on reports in the architectural periodicals.

[30] Information from Sunderland Civic Society.

[31] Sunderland’s Council records are mostly held at the Tyne & Wear Archives in Newcastle, but the relevant minutes of the Housing, Architectural & Estates Committee, 1963-64, were missing when the author visited in July 2007.

[32] Letters from J. Storey to Basil Spence, 14 and 26 October 1963, and 13 February 1964. R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS.

[33]Letter from Jack Bonnington to Storey, 7 August 1964; letter from Storey to Sir Basil Spence, Bonnington & Collins, 19 January 1965. R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS.

[35] Jack Bonnington submitted extension proposals to the Civic Centre Committee which would have provided these missing facilities, but they were never executed. See minute book, “Corporation of Sunderland – Civic Centre Committee – 6th June 1968 to 24th April 1972,” held in the Tyne & Wear Archives (4 June 1970; 25 February and 4 March 1971; 12 July 1973).

[36] Lance Wright, “Enquiries Welcome” in The Architectural Review, March 1971, pp. 161-62.

[37] The background to this section has been derived from Council minutes and files at the Local Studies Library, Kensington, and office papers in the Spence Collection, R.C.A.H.M.S..

[38] The site took its name from The Abbey, a gothic house built for William Abbott to the designs of Henry Winnock Hayward, and destroyed during the air-raids of 1940-41. For illustrations of both The Abbey and the neighbouring Red House, see Michael French, The Kensington & Chelsea Town Hall (published by the Directorate of Planning Services; no date).

[39] See contemporary press reports.

[40] Letter from F.H. Clinch, borough engineer and surveyor, to Basil Spence, 11 November 1964. Clinch had made an informal approach as early as 3 March. R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS.

[41] This was an ill-kept secret: although not official Council policy, an article favourable to the intended development appeared in The Kensington Post on 29 September 1967 (see p. 6).

[42] Letter from Spence to Clinch, 25 November 1964. R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS.

[43] See “Proof of Evidence of Sir Basil Spence” given to the Public Inquiry of 12 December 1967, R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS, and various other reports written in similar terms.

[44] “Message from Alderman C.A. Muller, Chairman, New Civic Buildings Committee” in the files at the Local Studies Library.

[45] Letter from Spence to John Waring Sainsbury, town clerk and borough solicitor, 15 June 1965. R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS.

[46] Letter from J.G. Osbourne to Spence. R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS.

[47] Letter from Clinch to Muller, 23 September 1965. R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS. The perspective was shown at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition of 1966.

[48] Letter from Godfrey Samuel, Secretary of the Royal Fine Art Commission, to Waring Sainsbury, 13 December 1965. R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS.

[49] “The Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea: Press Statement on the Proposed New Town Hall.” R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS. Also Builder, 11 February 1966, p. 273.

[50] See “Architects’ Notes: the John S. Bonnington Partnership” in the files at the Local Studies Library, and also “Bureaucratic Brickwork” in Building, July 1978, pp. 51-58.

[51] “Message from Alderman C.A. Muller.”

[52] See newspaper cutting files in the Local Studies Library. The 132% increase over Reynolds & Young’s estimate for the revised 1965 scheme reflected a substantial rise in building costs, approximately 44% during the intervening period, and the final scheme’s much greater floor area. (Source: Building, 21 January 1972, p. 73.)

[53] The following description has been based on the Architects’ Notes and press release, reports in contemporary periodicals, and the author’s own inspection.

[54] See Light & Lighting, May/June 1978, pp. 109-11 (copy in Local Studies Library). The pool was drained and planted as a flower-bed after water was found to be leaking into the car-park below. There remains some doubt, however, as to whether the water came from the pool itself, or from another source.

[55] This was lent to the Royal Borough by the Trustees of the Barbara Hepworth Museum at St Ives, Cornwall, following an approach by Councillor Muller. West London Observer, 19 May 1977, p. 11.

[56] Muller wrote to Spence on 9 March 1967 advising him that the Council had “approved your delightful bench and circular plaque for Sir Winston, but the cost did give some members rather a jolt as £1,500 to £2,000 was mentioned.” R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS.

[57] French, op. cit., states that solar-control glass was used on part of the south elevation only, and that all other windows were tinted to match.

[58] This was named after Niddry Lodge, which was demolished to allow the Town Hall to be constructed. It could function independently of the remainder of the building, and be leased for private use until required for Council purposes.

[59] The office planning consultants were Knight & Wegenstein.

[60] These ramps also provided a service entrance.

[61] Taywood News (Taylor Woodrow’s in-house newspaper), July 1977: copy in Local Studies Library. The counting system was designed and installed by Electronic Projects & Appliances Ltd, Ruislip.

[62] The raised-brick treatment derived from an earlier intention to line the stage backdrop with tapestry, possibly by John Piper or Edward Blunden. For details, see Taywood News, July 1977, and also a letter from Muller to Spence, 24 July 1965 (R.C.A.H.M.S. SBS).

[63] Evening Standard, 13 February 1975.

[64] “Background to the New Town Hall” in files at the Local Studies Library.

[65] For a savage financial analysis, see Paul Berry, “Kensington Palace Mk II – and the Cost to the Ratepayer” in Investors’ Chronicle, April 1977 (copy in Local Studies Library).