Persepolis: A Close Reading

Reading Repression

Marjane Satrapi’s episodic graphic novel tells the story of herself as a young girl growing up in post-revolutionary Iran. However, rather than a simple coming-of-age story Satrapi inserts the difficulties of

the political, religious, and economic strife that shaped her childhood and adolescence” (Tensuan, 956).

as major factors affecting her development. The comics explore the effects and responses to the ideological implementations of the Islamic theocracy, both through their narrative and their form. Satrapi’s graphics mirror the repression dealt with in her narrative. Persepolis has been highly acclaimed by critics, an interesting review by Andrew D. Arnold in Time Magazine described Satrapi’s work

It has the strange quality of a note in a bottle written by a shipwrecked islander. That Satrapi chose to tell her remarkable story as a gorgeous comic-book makes Persepolis totally unique and indispensable” (Arnold, Time Magazine).

Arnold's strange analogy is fitting to Persepolis as Satrapi conveys a world many Westerners have only experienced from a Western perseptive. She senstively and truthfully illustrates her development into a woman amongst the trauma of revolution, war and repression - redefining the importance of the graphic novel as historically and autobiographically informing.

The relationship between narrative and graphics.

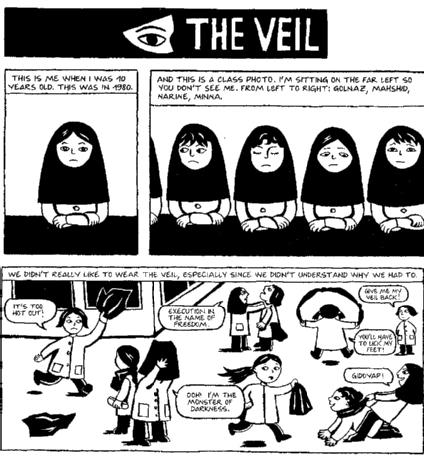

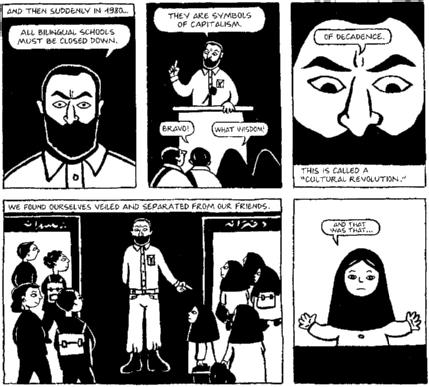

Satrapi’s black and white illustrations, for example, mirror the very repression that Marji and her friends and family face. For example, the veil is an extensively repeated image throughout Persepolis; and with it the illustrations seem to change. Whenever the children are depicted wearing the veil Satrapi’s graphics become plainer and unassuming – mirroring the uniformity of the girls.

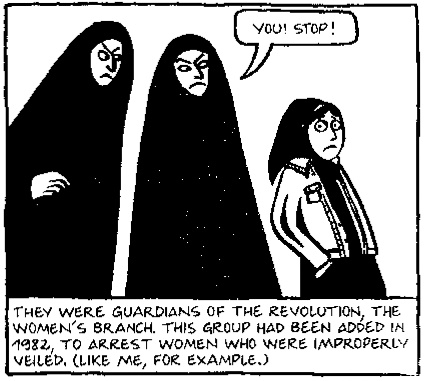

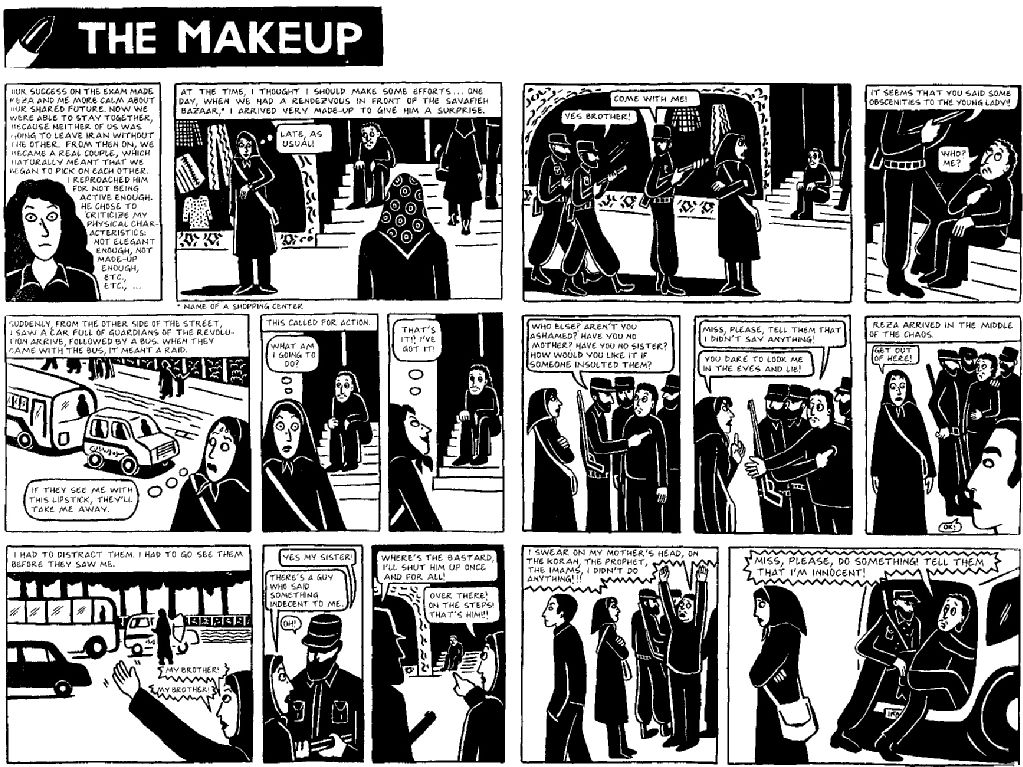

They are hardly distinguishable from one another, as they beat their chests to pay homage to their martyred “brothers”. Veiled women often appear in part one of the novel at moments of desperation and conflict. For example, the illustration below shows Marji being accosted and interrogated by two Guardians of the Revolution for being improperly dressed.

They are hardly distinguishable from one another, as they beat their chests to pay homage to their martyred “brothers”. Veiled women often appear in part one of the novel at moments of desperation and conflict. For example, the illustration below shows Marji being accosted and interrogated by two Guardians of the Revolution for being improperly dressed. The Guardians look unearthly and imposing as they tower above little Marji in their floor-length veils. This image shows how the veil was an empowering tool for women aligned with the regime, as they wore it with self-imposed superiority. Thus, the veil is both a weapon of oppression (victimising women by repressing individuality) and of superiority – mirrored in Satrapi’s graphics.

The Guardians look unearthly and imposing as they tower above little Marji in their floor-length veils. This image shows how the veil was an empowering tool for women aligned with the regime, as they wore it with self-imposed superiority. Thus, the veil is both a weapon of oppression (victimising women by repressing individuality) and of superiority – mirrored in Satrapi’s graphics.

Escaping repression.

Yet, as much as these characters and their freedom of expression are repressed, Satrapi’s graphics show exactly how the Iranians escaped and rebelled against such repression.As Theresa Tensuan states:

Satrapi’s comics highlight the ways in which figures resist, subvert and capitulate to forces of social coercion and normative visions” (Tensuan, 954).

And so, having shown how the Iranians are forced to surrender to the Islamist theocracy, it is worthwhile exploring how they rebel against it. For example, the juxtaposition of the two images below perfectly exemplifies the expected and actual responses to the introduction of the veil.

The first shows Marji (Satrapi) and her schoolmates in a row, looking bored; whereas the image below shows them playing raucously in the playground – using their veils as skipping ropes, reigns for playing pony and generally using them as props in their various games. Furthermore, when Satrapi is a young adolescent she rebels against the anti-western ideal of her Islamic State by asking her parents to bring her posters and clothes back from westernised Turkey. They bring her a pair of Nike trainers and a denim jacket with a Michael Jackson button on it – an outright violation of the dress code, this is what the Guardians of the Revolutions question her about (see image above). In her childhood Marji is pictured as overtly rebelling to the

sartorial censorship” (Tarlo, 9)

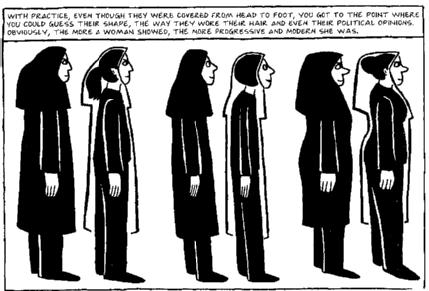

imposed by her government. However, as she grows up and returns to Iran from Austria rebellion through fashion had become more subtle and harder to detect. For example, women would style their hair differently under the veil so their veils would have different appearances and shapes:

This variation in veiling shows how Iranians developed a way of communicating their views and opposition without directly breaking laws of the theocracy.

This variation in veiling shows how Iranians developed a way of communicating their views and opposition without directly breaking laws of the theocracy.

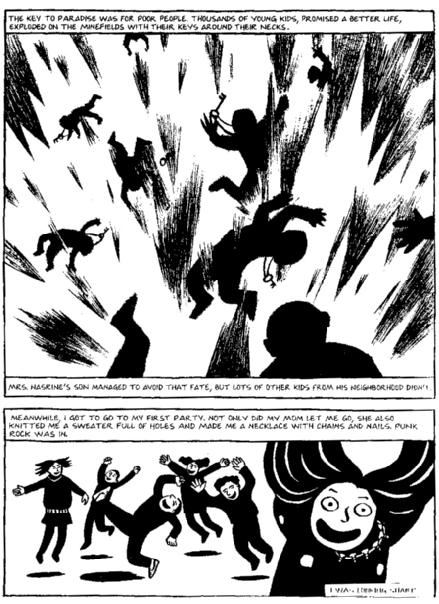

However, Satrapi also shows how their opposition to the imposed repression (by holding illegal parties with bootlegged alcohol) was juxtaposed by the persecution of young male soldiers, who were sent off to war as cannon fodder just because they were poor:

The positions of the children dancing and the blown up soldiers are almost entirely identical to each other. At least she, her friends and family can rebel in their own ways unlike these brainwashed teenage soldiers – tricked into believing the plastic keys painted gold that they wear will send them straight to paradise. Thus, Satrapi indicates her rebellion as insignificant as innocent boys were still dying in the name of Iran – they could not escape their persecution.

The Movement of repression.

The theme of repression is an ever-changing, shifting issue within Persepolis. As shown, Satrapi illustrates the way Iranians were repressed in public spaces and by public figures. The image below shows a bearded Islamist explaining the implementation of the Veil, as an anti-Western device:

Showing how the theocracy attempted to enforce their ideals: they believed by enforcing uniformity they would eradicate Western influences, particularly the ideal of the individual. Through diluting individualism, they could claim Islamic absolutism. However, her home was a place of free expression. This is reflected in her childlike understand of the revolution and her graphics – which become much more expressive and fluid:

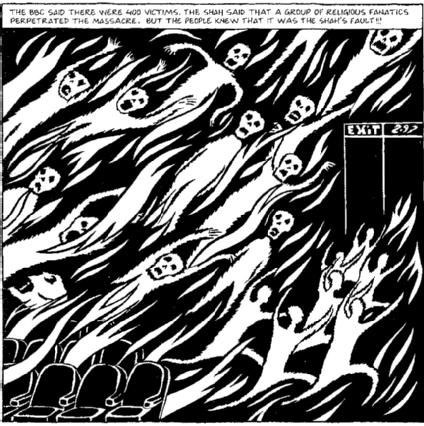

This harrowing image, a child-like interpretation of a massacre at a cinema, is sensationalised as the dying people become like an extension of the flames which engulf them. Hilary Chute refers to this idea in her article:

This is clearly a child’s image of fiery death, but it is also one that haunts the text because of its incommensurability – and yet its expressionistic consonance – with what we are provoked to imagine is the visual reality of this brutal murder.

(Chute, 100)

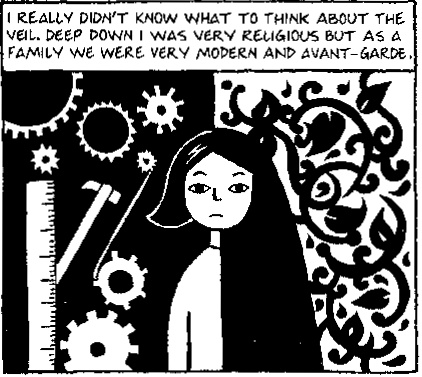

Hence, Satrapi’s haunting images are sensational – an evocative, stimulating yet shocking glimpse into the mind of a child of the revolution. Yet, despite her evident disgust at the killings by radical Islamists, Marji clearly still relates to Islam. Satrapi also depicts herself as torn between these two worlds: the forwards, liberal-minded world of her parents and her religiosity:

One half of the image shows her surrounded by cogs, a hammer and a ruler – implying the influence of the mechanics of her “avaunt-garde” family. The other half, shows her fully veiled and surrounded by elegant Persian patterns, referring to the ancient traditions of her religion; Marji idealises Islam yet not in the same way the state follows. And so, as much as Marji revels in the rebellion against the theocracy – she feels torn between the religion she idealises and her liberalism.

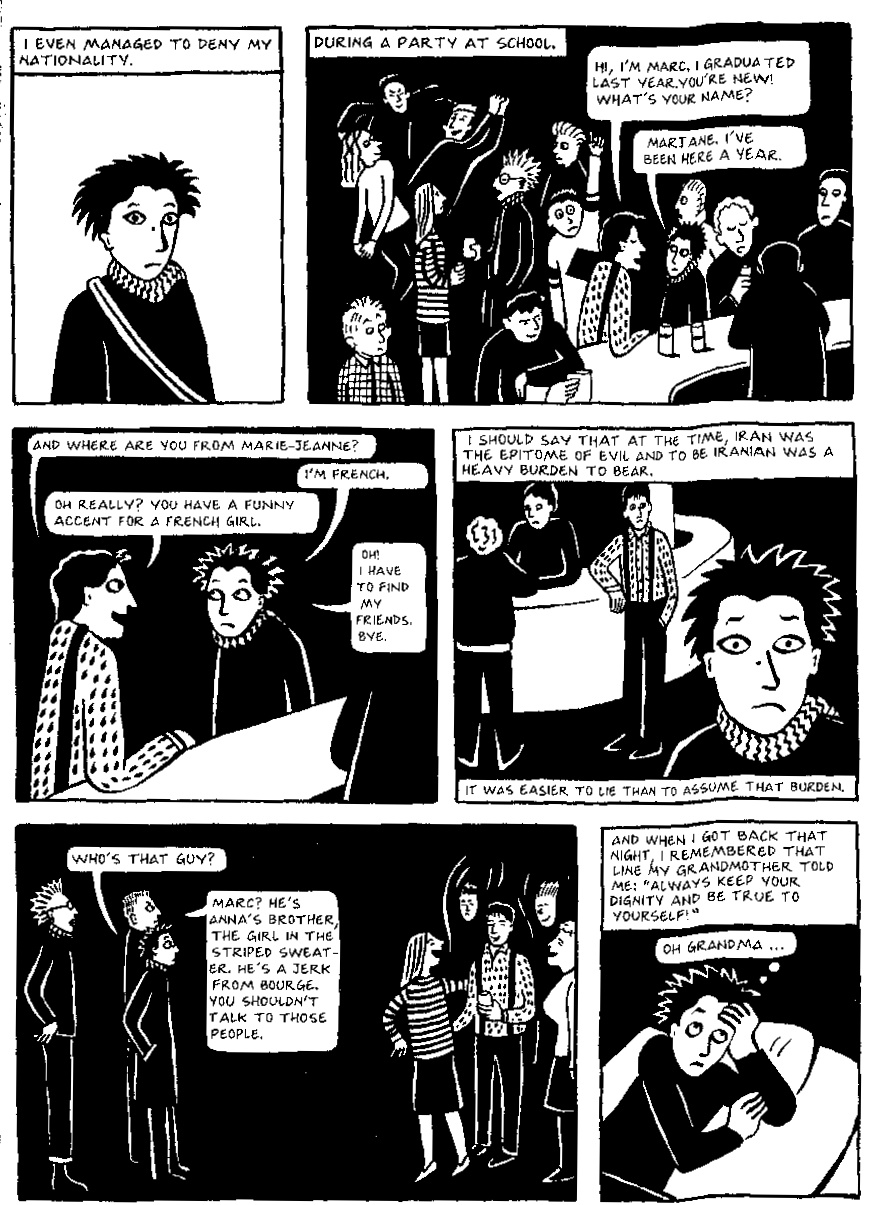

The story then moves to Vienna, Marjane, escaping the war in Iran finds herself in an alien environment. As Tarlo recognises: “The veil provides a subtle affinity between the nuns and the fundamentalist women she left behind in Iran, and Satrapi implies that the affinity is more than simply visual” (Tarlo, 5):

From here, she is thrown out of the convent - directly mirroring the tyranny fundamentalist Guardians of the Revolution in Iran. She begins to lose her way and not only forget who she is but repress herself. Persecuted for being Iranian, she begins to accept her role as the other and in a desperate attempt to fit in she abandons her identity and tries to pass as French, to impress a boy:

Satrapi’s perception of herself keeps fluctuating; she at once identifies herself as being other and so desires to conform with the Europeans. This moment shows Marjane repressing herself, thereby illustrating repression can come from within oneself as well as from external forces.

Finally, after a very adolescent downwards spiral (including a lover, drugs, a break-up and a bout of homelessness) Marjane returns to Iran. She, at first, feels alienated by her child-sized room and overwhelmed by her welcome home. However, after realising the subtle rebellion the other young women employ, Satrapi transforms herself: perms her hair, wears make-up, runs an aerobics class and parties. There, she meets Reza and together they gain admission to a prestigious art course at university. Together they become more confident about defying laws, so much so that Satrapi dares to meet Reza in public wearing noticeable make-up. However after spotting Guardians of the Revolution Marjane panics:

She cowardly accuses a stranger of a graver crime than her own rather than face the consequences of her rebellion. Hence, now Marjane becomes the unjust agent of repression – resembling those that she protests against.

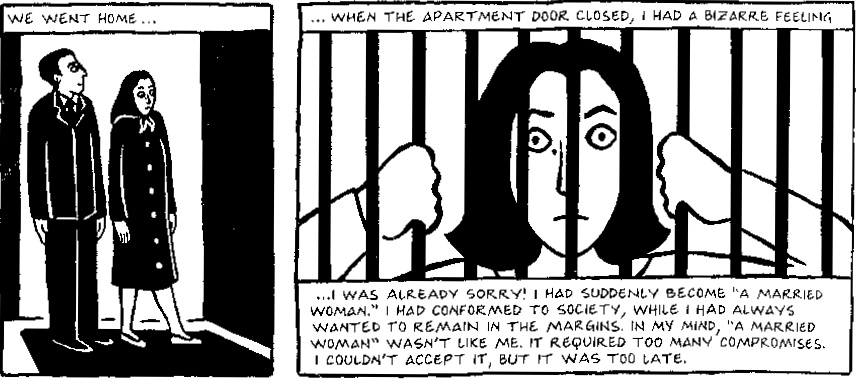

Yet, in the end, Marjane and Reza became fed up that they could not publically show their relationship –unmarried couples could not display their affections, as pre-marital affairs were illegal. Consequently, in an attempt to escape the repression of their relationship, Marjane and Reza marry. Yet, Marjane’s regret seems almost instant; she abruptly recognises her mistake. She feels caged by their dwindling communication and eventually feels trapped by that which was meant to free them. She is depicted as litterally caged:

Ultimately Satrapi’s journey, at all stages, is affected by repression. She and fellow Iranians suffer political oppression – repressing their personal freedoms; she experiences self-inflicted persecution as an outcast in Vienna; she momentarily becomes a similar agent of repression to those she hates and finally enters a marriage where she feels isolated and imprisoned. Therefore, Satrapi not only effectively and historically illustrates the trauma of war and political oppression but shows the personal (and sometimes unexpected) consequences of trying to escape repression. Her illustrations, often artistically reflecting her narrative, are charming and engaging – her novel is a testament for the power of the graphic novel in representing political and personal turmoil.

Marianne Matusz

Works Cited:

Arnold, Andrew D. “An Iranian Girlhood” Time Magazine. 16/05/2003. Web. 19 May 2013.

Chute, Hillary. "The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis" WSQ: Women's Studies Quarterly 36.1 (2008): 92-110. Web. 16 May 2013.

Tarlo, Emma. "Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis: A Sartorial Review." Fashion Theory 11.2-3 (2007): 347-356. Web. 18 May 2013.

Tensuan, Theresa M. "Comic visions and revisions in the work of Lynda Barry and Marjane Satrapi." MFS Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (2006): 947-964.

Works Consulted:

Davis, Rocío G. "A Graphic Self: Comics as Autobiography in Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis." Prose Studies 27.3 (2005): 264-279.

Ellis, Samantha. “Less of Your Lipgloss” The Observer. 7/11/2004. Web. 19 May 2013

Whitlock, Gillian. "Autographics: The Seeing" I" of the Comics." MFS Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (2006): 965-979. Web. 16 May 2013.

Naghibi, Nima, and Andrew O'Malley. "Estranging the Familiar: East and West in Satrapi's Persepolis." ESC: English Studies in Canada 1.2 (2005): 223-247.