The Irish, Politics and Sectarianism in Nineteenth-Century Liverpool

Laura Kelly

The hundreds of thousands of Irish migrants who arrived in Liverpool after the 1840s placed a huge strain on the city’s resources and were charged with spreading disease, raising poor rates, and increasing pressure on scarce working-class housing. Irish migrants in Liverpool encountered a broader culture of anti-Irishness which related to the squalid state of the districts they inhabited. Contemporary newspaper reports refer to the rising death rate among the Irish population and the severe strain placed on the city’s basic social service structures. The Irish in Liverpool were also linked to the rising incidence of well-documented social evils such as pauperism, alcoholism, violence, crime, vagrancy, prostitution, and declining wages, with this association continuing well into the late nineteenth century. In 1871, for example, the Irish-born accounted for 33.4 per cent of arrests in Liverpool, and similar figures exist for other Lancashire towns. At times of scarcity of work in Lancashire, anti-Irish sentiment intensified. The Irish were portrayed as depressors of wages because they were allegedly willing to work for less pay than their English counterparts, and they were also used as strike-breakers. Moreover, to working-class inhabitants of Liverpool, in particular, unskilled labourers who relied on casual day labour, Irish migrants were seen as competitors for work and accommodation in inexpensive, overcrowded and unhealthy housing in the city. Prejudice against the Irish intensified in the 1860s with the press being instrumental in the creation and reinforcement of stereotyped biases of the Irish, perpetuating a popular image of the Irish as being childish, lazy, violent, superstitious and unintelligent.

Anti-Catholic sentiment was an important strand of anti-Irishness which was expressed in vocal and sometimes violent opposition to the Irish. Religious sectarianism was a major problem and by the end of the 1850s, Liverpool’s working class, was, according to Frank Neal, divided ‘in a way that was unique to England’. Anti-Catholic sentiment in Liverpool strengthened internal Irish solidarity while also delaying their acceptance by the community at large. Police court reports and the published accounts of clergymen who visited Liverpool’s slums paint a picture of great bitterness resulting from the religious polarisation of the city. Bitterness and divisions found expression in fights, brawls and riots and these were not confined to male participants. For example, in November 1847, Mary Kelly was responsible for leading an Irish mob in an attack on a Protestant chapel in Bishpam Street. The windows of the chapel were broken and the congregation was stoned, with Kelly remarking in court that she ‘would die for her religion’. Similarly, in March 1852, police were called to a pub in Lime Street where a fight had occurred between two women over a religious squabble, and all of the windows in the pub broken. Mixed marriages between Catholic and Protestant members of the working-class also presented problems. Reverend Francis Bishop, who was in charge of the Liverpool Town Mission wrote in his report for 1849 of ‘the evils of sectarianism’ and drew attention to the bitterness produced by sectarianism in working-class life:

I have seen the ‘evangelical’ Protestant husband and Catholic wife, giving loose to their passionate bigotry in actual personal conflict with each other; I have heard the Pharasaic and unfeeling man taunt his dying wife with her attachment to ‘Popery’. I have known homes to be broken up from the same cause, husband and wife to be separated, and the most unseemly contests carried on respecting the division of the children; and of feuds and ill blood between neighbours, springing from the roots of bitterness – I am constantly seeing instances. (quoted in Neal, p.160)

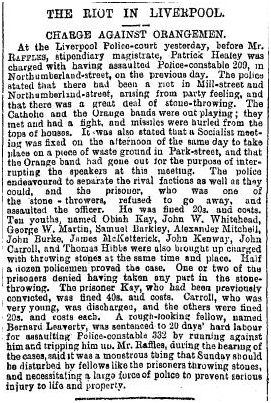

Anti-Catholic sentiment was promoted by the Orange Order. The Order, first established in Armagh in the north of Ireland in 1796 with the aim of standing by Protestantism and the Crown, spread to England. Although banned in England in 1836 due to its association with sectarian violence and infiltration of the military, it was revived in the 1840s and gained particular popularity in Liverpool. The Liverpool Orange fraternity increased in size between 1850 to 1860 and at the Grand Lodge of the Orange Institution, held in July 1860, twenty-eight of the thirty-four officials who attended were from Liverpool. The 12 July became a holiday celebration for the working-class Protestant community in Liverpool participating in marches and processions which moved to the Liverpool countryside after 1852. They soon became an annual outing for slum-dwellers of the City. These trips were characterised by heavy drinking with the potential for brawls following the return to the borough. On the 12 July 1876, the biggest Orange procession in English history took place in Liverpool with 7,000 to 8,000 Orangemen taking part. Political campaigns exacerbated the tense atmosphere – The Home Rule election campaign of 1886 resulted in an increase in sectarian violence on the streets of Liverpool. For example, in July, at the end of polling, an Orange band marched from Toxteth to Lime Street, accompanied by a large crowd. The mob stoned the Catholic church, St Patrick’s, breaking many windows, with the Irish soon retaliating and causing damage to Protestant churches in Toxteth. Catholics took part in attacks on Protestant funerals, such as in 1852, at the funeral of an Orangeman in Toxteth, where an Irish mob, armed with sticks and stones, gathered in the streets near the home of the deceased, ready to attack the mourners at the funeral. Upon hearing of the planned attack, a large group of Protestants joined the crowd of mourners and a violent fracas occurred where the Irish were beaten. In the 1840s, St Patrick’s Day parades in Liverpool often involved public demonstrations and disturbances by the Irish. However, these were banned in 1852, along with Orange processions, and in the 1860s and 1870s, when the parades were resurrected, they became more sedate affairs, in part, as a result of efforts on the Liverpool clergy.

William Nott-Bower, Head Constable of Liverpool City Police (1881-1902) wrote of his time in Liverpool in the 1880s:

Liverpool was peculiarly situated as regards the Irish question. A large district of the town was quite as Irish as any district in Dublin and ‘Nationalists’ and ‘Orangemen’ were as strongly represented and as antagonistic as in Belfast. (quoted in Neal, p.187)

By the 1880s working-class Liverpool was more divided than in the 1840s and religious sectarianism persisted as an aspect of working-class experience in Liverpool into the late nineteenth century.

Politically, the Irish in Lancashire, up until the 1860s, represented a distinctive group and their political activism tended to centre on Irish national issues rather than British politics more generally. There were two main political movements in Lancashire in the mid-century, the Irish Confederates (a short-lived nationalist group founded by the Young Irelanders) and the Fenians; both of these groups were secret nationalist organisations. While the Irish Confederates disappeared almost without trace after the 1840s, the Fenians, or Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), came to prominence from 1858. This organisation had one main goal, Irish independence to be attained through an armed rising. The Lancashire branches of the Fenians represented its largest and best-organised centres of activity and held regular meetings in public houses, helping to solidify Irish emigrants’ sense of identity and allow Lancashire Irishmen to feel that they were doing their bit to plan and support an Irish rising. In 1867, the arrest and hanging of three members of the Manchester Fenians – Michael Larkin, William Allen, and Michael O’Brien – known as the Manchester Martyrs, for the killing of Sergeant Brett, strengthened Irish community solidarity and nationalism in Lancashire. In the 1870s and 1880s, the IRB provided a foundation for support of Land League agitation and the Home Rule movement while the Fenian network which centred on the parish-based social life of the Lancashire Irish allowed for Irish national issues to be widely disseminated in local Irish communities in England.

Further reading

W.J. Lowe, The Irish in Mid-Victorian Lancashire: The Shaping of a Working-Class Community (Peter Lang, 1989), chapters 6 and 7.

Frank Neal, Sectarian Violence: The Liverpool Experience, 1819-1914: An Aspect of Anglo-Irish History (Manchester University Press, 1998).

An account of a sectarian riot in Liverpool, Leeds Mercury, 21 September 1886