"Shattered in bodily health and condition": Treatment and the Irish in Nineteenth-Century Lancashire Asylums

Stephen Bance

The processes of treatment and management considered suitable for the lunatic insane underwent a transformation in the 1800s. The older view that the essence of madness was the absence of reason was rejected and replaced with a pragmatic approach that recognised the patient as a moral subject. Likewise, the treatment techniques of madhouse keepers, which included ‘vomits, purges, surprise baths, copious bleedings and meagre diets’, were viewed as inappropriate methods of management in the nineteenth century. Instead, new systems of ‘moral treatment’ that considered the patient ‘as much in the manner of a rational being as the state of his mind will possibly allow’ emerged. In England moral treatment was associated with William Tuke and the York Retreat, which was established in 1796, where many of the methods were first practised.

Leather restraint harness which restricted the movements of mentally ill patients considered violent. More humane methods of management were introduced throughout the 1800s as instruments of mechanical restraint were renounced in favour of ‘moral treatment’. Wellcome Library, London

As Anne Digby has shown, the Victorian ethics of hard work and Christianity underpinned both the structure of society and consequently the management of the asylum system. At the York Retreat, employment was a key component of moral treatment and it was thought that distraction through routine or productive work helped relieve the symptoms of depression (melancholia) and promoted self-control. For female inmates, tasks included sewing, making clothes for the patients, laundry work or cleaning. Activities for male patients included carpentry, gardening or other outdoor work. The attendants who supervised patients were selected because they had vocational skills such as gardening, joinery or agricultural skills, which could be utilised to help provide occupational therapy for patients. Better quality food was seen as essential in improving the mental and physical well being of patients. Exercise was considered beneficial and patients were encouraged to walk and benefit from fresh air and sunlight. Entertainments such as dances, concerts and sports days were arranged for patients, and items such as newspapers, magazines and books were supplied. Constructive hobbies and talents, such as bird-keeping and playing music, were also encouraged.

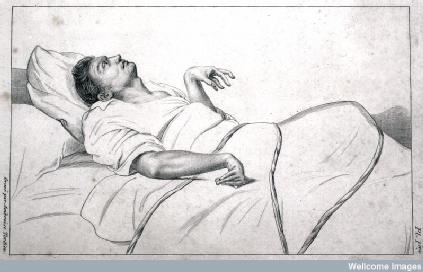

Patient suffering from melancholia (1837), Wellcome Library, London

Many of the new public asylums built in the nineteenth century, including Hanwell in London and Lancashire’s four public asylums (Lancaster (1816), Rainhill (1851), Prestwich (1851) and Whittingham (1873), attempted to implement the practices of moral treatment. However, as the public asylum system became progressively overcrowded, the practical implementation of moral treatment became unsustainable. Bowing to political and social realities, the medical superintendents of asylums compromised, as management was prioritised over treatment. The more expensive aspects of moral treatment were diluted – the pleasing and cheerful architecture, considered important in creating a curative atmosphere was often replaced by monotonous, prison-like asylum buildings. By the mid-nineteenth century, many of the new asylums were much larger than those originally envisaged by Tuke, and the degree of regimentation needed to administer these institutions meant that they became the antithesis of moral treatment methods. In addition, while early moral managers criticised the use of medical therapeutics, opiates were widely used and after the 1860s sedatives were more regularly prescribed. The sacrifice of routine to the needs of the individual, a central pillar of moral treatment, became secondary to the administrative needs of the institution.

An insane patient in an asylum (1838), Wellcome Library, London

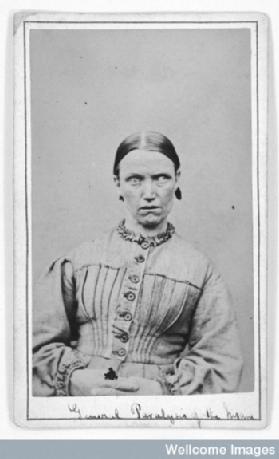

At the Lancashire asylums, and especially Rainhill, the presence of large numbers of Irish patients contributed not only to overcrowding, but the Irish were also perceived to be a group who were particularly resistant to the strictures of moral management. By the late nineteenth century Irish patients had become increasingly associated with ‘mania’, disruptive and violent behaviour and the taints of degeneration, making them difficult patients to manage. Due to their assumed defective mental organisation, the Irish were more likely to fall into the category of ‘incurable’ and were deemed particularly susceptible to ‘general paralysis of the insane’, which was associated with intemperance, low morality and criminality. Asylum medical superintendents asserted that general paralysis was prevalent in large urban centres, with their poor conditions and opportunities for vice and corruption. The rural Irish, in comparison, were described as being free of the condition, but were very likely fall prey to it up once they arrived in Liverpool. Catherine Cox and Hilary Marland note that over time the typical character of general paralysis changed from younger males, to ‘older, broken down, demented, filthy, voracious creatures’ who could survive long periods. The burden shifted from managing furious and violent characters to caring for the long term degraded sick.

Among Irish patients generally, but particularly among patients diagnosed with general paralysis, death rates were high and discharge rates low. While work was a key aspect of moral management, many chronic, Irish patients could not contribute to the asylum workforce. The optimism that accompanied the opening of Lancashire’s asylums had dissipated by the 1880s, as the asylums rapidly reached capacity and underperformed in terms of recovery and discharge. As a category of patient in the Lancashire asylum system, the Irish exacerbated these problems, as they provided particular numerical, physical and social challenges in terms of treatment and management.

Woman suffering from 'general paralysis'. West Riding Lunatic Asylum, Wakefield, Yorkshire (c.1869),

Woman suffering from 'general paralysis'. West Riding Lunatic Asylum, Wakefield, Yorkshire (c.1869),

Further Reading:

Catherine Cox, Hilary Marland and Sarah York, 'Emaciated, Exhausted and Excited: The Bodies and Minds of the Irish in Nineteenth-Century Lancashire Asylums', Journal of Social History 46: 2 (2012), 500-24.

Catherine Cox, Hilary Marland and Sarah York, ‘Itineraries and Experiences of Insanity: Irish Migration and the Management of Mental Illness in Nineteenth-Century Lancashire’, in Catherine Cox and Hilary Marland (eds), Migration, Health and Ethnicity in the Modern World (Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 36-60.

Anne Digby, Madness, Morality and Medicine: A Study of the York Retreat, 1796-1914 (Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Barry Edgington, ‘Moral Architecture: The Influence of the York Retreat on Asylum Design’, Health and Place, 3: 2 (1997), 91-9.

Andrew Scull, The Most Solitary of Afflictions: Madness and Society in Britain, 1700-1900 (Yale University Press, 2005).

David Wright, ‘Getting out of the Asylum: Understanding the Confinement of the Insane in the Nineteenth century’, Social History of Medicine 10:1 (1997), 137-55.