Professor Ian Goodfellow Working in Sierra Leone to combat Ebola

Renowned virologist Professor Ian Goodfellow, graduated from Warwick in 1993 with a degree in Microbiology and Virology. After gaining his PhD from the University of Nottingham, Professor Goodfellow was awarded a Wellcome Trust Fellowship at the University of Reading. In 2006, Ian moved to the Section of Virology at Imperial College where in 2012 his Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship was renewed and he moved to the Pathology Department at the University of Cambridge, his current research base. During the recent Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, Ian was a part of the team of British volunteers who risked their lives to deliver much needed help to the medical services.

My main research focus is virus-host interactions, focusing primarily on noroviruses, the major cause of gastroenteritis in the developed world. We’ve used a variety of approaches to try to understand the viral life cycle and more recently have taken the first steps towards the identification of therapeutic approaches for the control of norovirus infection in patients. My interests have recently spread into other areas of virology such as the zoonotic potential of viruses and host responses to viral infection.

I made the decision to go to Sierra Leone during the late summer of 2014 after following the media coverage of the Ebola outbreak closely over the proceeding months. The coverage was harrowing, particularly for a virologist, as I understand how, with the right expertise and infrastructure, it is relatively easy to contain Ebola. The combination of urbanization and underdeveloped healthcare systems created a ‘perfect storm’ type scenario for Ebola to establish a foothold in West Africa.

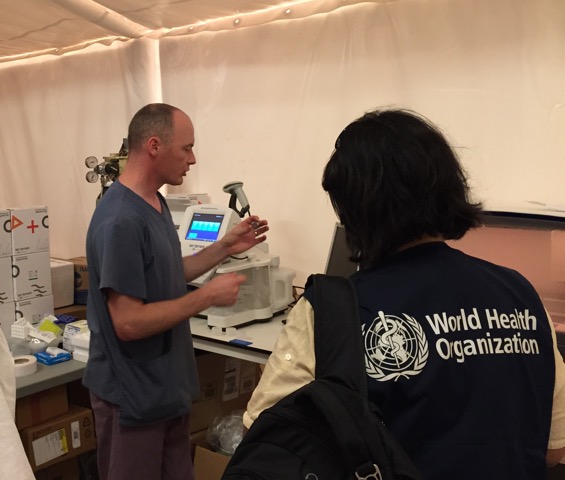

I was in Sierra Leone for around five weeks and the first impressions were much better than I had thought. The few media reports that made it to the UK during the summer would lead you to believe that the epidemic had caused an almost complete breakdown of society in Sierra Leone. While there was a clear impact, the vast majority of the population appeared to be going about their everyday life as normal. I was part of a team of 10 volunteers from various parts of the UK sent by Public Health England (PHE) to establish a diagnostic facility in Makeni. We were the first team to be deployed to Makeni and we deployed under the umbrella of International Medical Corps to work at an Ebola treatment centre (ETC) built by the Royal Engineers and funded by Department for International Development.

The team was made up of several biomedical scientists from the UK, research staff from PHE Porton Down and two academics from UK universities. We spent one-week training at Porton Down prior to our deployment. The training team at Porton Down were fantastic and provided us with an excellent grounding in the procedures we would use in the lab. The first week or two was spent primarily moving equipment by hand around a very busy building site. Equipment and reagents would turn up on the back of lorries and need to be manually unloaded. Moving several tons of equipment and reagents around the site manually in the heat and humidity was very difficult but the team managed well. There were a couple of cases of heat stroke, lots of blisters and bruises, but the team all worked together to get the job done.

One of the main difficulties was trying to determine who had Ebola and who did not as there are many other diseases that have similar symptoms – malaria being one of them. Prior to laboratory confirmation, the patients are often kept in hospitals or holding centres, which typically contain a mix of both Ebola positive and negative patients. As soon as a patient is confirmed, they are then moved to an Ebola treatment centre. Every minute an Ebola positive patient spends in a holding centre with patients that do not have Ebola, greatly increases the chances of the disease spreading further. Therefore, there was an urgent need to speed up the time between the samples being collected to the lab results being reported. This was also true for any deaths in the community; all corpses were swabbed and tested. If the results were positive, then the entire family were placed in quarantine and monitored for 21 days. The three purpose built PHE laboratories more than doubled the diagnostic capacity of Sierra Leone and results were now typically reported back to the clinicians the same day the samples were taken. Previously this would have typically taken two to five days.

I feel incredibly fortunate to have been able to make a small contribution towards the efforts to control the epidemic, however there is a lot of work still to be done. The epidemic has had a huge impact on both the healthcare system and the economy of all the countries involved. It will be sometime before we know the true impact of the epidemic but its effects stretch much further than the individuals that were infected.